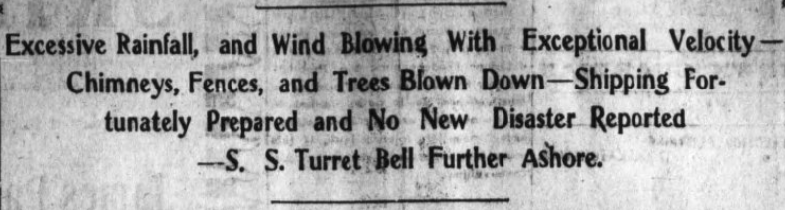

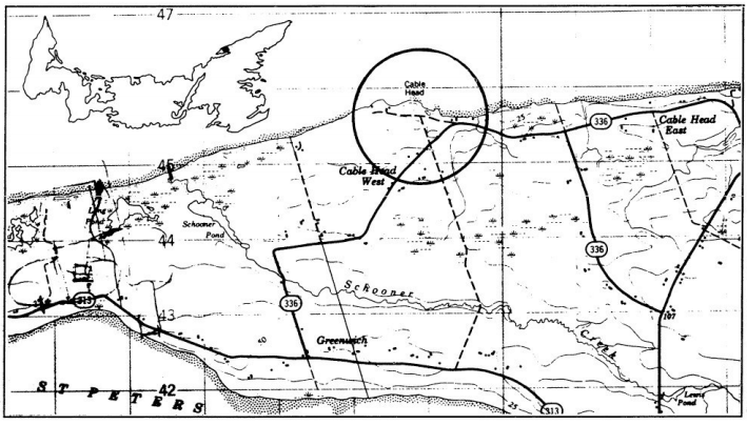

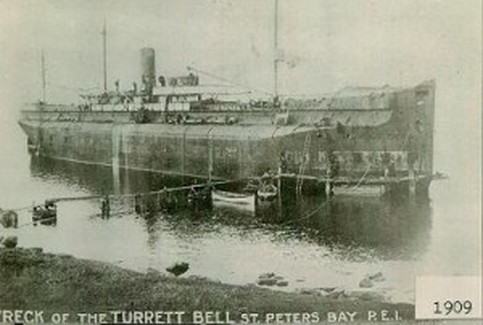

The rocky shoreline of Cable Head today. Reproduced under fair use from Beachcombers Haven Cottage. The rocky shoreline of Cable Head today. Reproduced under fair use from Beachcombers Haven Cottage. Note: This is part one of our on-going series about the shipwrecks of Northeastern Prince Edward Island. The first three in our series will focus on those ships wrecked during the November Gale of 1906. The November Gale of 1906 is well remembered by those who still live alongside the northeastern coast of Prince Edward Island. It was this gale that was responsible for the infamous wrecks of the Turret Bell, The Sovinto, and The Olga, among others. Within a twenty-mile span, from Priest Pond to Cable Head, four ships alone were wrecked in the storm. It was a storm that could not have been predicted, for The Guardian of 5 November 1906 wrote that "even weather vanes were deceived. The barometer gave no warning; the weather possibilities conveyed no hint of more storms..." Despite this, the November Gale raged on for almost two weeks, and dumped eight inches of rain upon the area. It is in these conditions that we turn to the story of our first wreck. The Wreck of the Turret Bell. Built in 1894, it was of the “whaleback design” which had evolved out of necessity of shipping on the Great Lakes during the 1890s. Bulky and off-putting, these whaleback steamers were renowned for their unconventional design. However, it was to be the case that this very design would be the thing to put the wreck of the Turret Bell on the map. An Unexpected Occurence. The Turret Bell’s story began on an unremarkable day in the late autumn of 1906. Her Captain, a Mr. Murcassen, was guiding her down the St. Lawrence river, en-route for Cape Breton to retrieve a load of coal. But as she entered the Gulf of St. Lawrence, the Turret Bell sailed straight into one of the worst storms in Island history. High winds quickly developed as the ship sailed along, and it was in little time that the Turret Bell was blown far off her course. Visibility was low, and navigation nearly impossible. The Captain did his best to keep his ship on course, but the storm had other plans for her on that fateful day, and before Captain Murcassen knew it, the Turret Bell had been wrecked upon a rocky ledge, her bow pointing landward, 150m offshore at Cable Head, near St. Peter’s Bay. There were 22 souls on board. Their only salvation was that the broad bulk of her whaleback hull was enough to keep her upright in the shallow water, despite the whipping winds and raging seas. It was early Friday morning, 2 November 1906.  The Guardian, too, detailed the ferocity of the storm. The Guardian, too, detailed the ferocity of the storm. Islanders Discover the Wreck. News of the wreck spread across the Island as that day’s edition of the Daily Examiner ran the headline: "ASHORE AT CABLE HEAD. BIG LINER TURRET BELL ON ROCKS. DOUBTFUL IF SHE WILL BE ABLE TO GET OFF." The account continued, describing the severity of the wreck: “The steamer is firmly wedged upon a bottom of rock and is resting on an even keel. She is lying about 150 yards out from the shore and does not appear to be pounding. A very heavy sea is still running and, although there seems to be no danger of the steamer breaking up, yet the distance to which she has been driven in to the shore makes it look doubtful if she can be floated again. Owing to the heavy sea on, no communication has yet been made with the steamer from the shore and it has been impossible to launch a boat.... A large number of men went from Souris to Cable Head this morning but were unable to render assistance owing to the severity of the weather...”  A map indicating the location of Cable Head. Government of Prince Edward Island. A map indicating the location of Cable Head. Government of Prince Edward Island. A Rescue Attempted. Efforts were put underway to send a tug-boat to rescue the doomed steamer, but it quickly became apparent that to do so would be impossible, and that the Turret Bell could not be tugged out, as it was “lying well within the sandbar.” Up to this point, it had remained impossible for any communications to be made from the shore to the men trapped onboard the ship. The storm had worsened that night, and a high tidal surge had washed her further inward toward the shore, leaving her about 20m offshore. Despite the ship's proximity to land, strong winds and currents prevented any means of escape for those trapped on board, and although they were closer than ever to safety, the hope of a rescue still evaded them. Questions soon arose as to the safety and conditions of the men, and as to whether they had adequate food stores. To remedy this, Captain Murcassen cleverly established communications with those on shore by sending dispatches in a bottle. This one way communication system was not ideal, but it was enough to serve the purpose. He advised those on land that the crew were dry and comfortable, and that they had sufficient provisions on board. Those on board remained there for the weekend, and by Monday morning, as the weather grew calmer, it was possible to bridge the 20m span with a cable. Through the use of this cable the Captain came ashore that morning, and later that evening his wife, who it was revealed had been a passenger on the ship, came ashore as well. The crew remained on the ship until the next morning. Salvaging a Colossus. With all those who had wrecked upon the Turret Bell present and accounted for, the skeleton of the doomed steamer became a phenomenal tourist attraction for those in the surrounding area of Eastern Kings County. As Townshend remarks, “People came on foot and on horseback, by horse and carriage, and (a very few) by car.” This curiosity, the sense of inquisitiveness which is at the heart of every Islander, too gave way to create an enduring part of this story, as it was from these numerous visits that the Turret Bell Road, a road which remains in use to this day, became developed as it is. Initially, curious onlookers travelled north on the Greenwich Road towards the dunes area on the seaward side of the St. Peters peninsula, and then made their way across the beach. This route to access the site proved to be tedious and ineffectual. Later, when efforts to re-float the ship got underway, “a new road was cut through the woods on the Sutherland farm, at right angles to the Greenwich Road, to provide a more direct route to the site of the wreck.”  The Turret Bell Road today. It now leads to cottages and summer homes. The Turret Bell Road today. It now leads to cottages and summer homes. This clay road, which was intended only for those working on the reclamation of the ship, became a popular shortcut for those wishing to see the wreck, and hence its legacy remains even today. Even with the facilitation of the Turret Bell road, the salvaging of the Turret Bell proved to be difficult business. The sheer size and weight of the vessel, coupled with its proximity to shore, offered a foreboding challenge to those who sought to right it. Furthermore, salvage machinery was, at the time, in short supply, and the window of favorable weather in which to conduct such operations was deceptively short. After two long years a crew had managed only to dislodge her from her holdings, and to float her 700 feet from shore. This was seen as good news, but Winter was upon them, and so the Turret Bell was pumped full of water to anchor her in place, and a man was assigned to live onboard her over the winter. Recovery efforts resumed in the spring time, and by the summer of 1909 she was prepared to be hauled to Charlottetown by a tugger, and to the surprise of everyone she was able to assist in her own propulsion, as her steamers still remained operational after all that time. Amazingly, after three years (and three winters) at Cable Head, the Turret Bell was in sound and sturdy condition after her time at Cable Head, aside from being outwardly rusted. On 13 August 1909, the Turret Bell, again under tow, left Charlottetown for Quebec. She was due for repairs, but after maintenance and restoration would was to be put back at sea, a successful end to a memorable wreckage. To discover more about the Island's hidden history, from shipwrecks and rum-runners, wishing wells and ghost stories, visit the Red Rock Adventure Company home page, and learn about all the touring opportunities which we offer. This project is made possible through a partnership with the Red Rock Adventure Company and the Sourispedia Project. Sources: 1. Townshend, Adele. "Survivor: The Wreck and Salvage of the Turret Bell." The Island Magazine. 2. St. Peter's Bay Community Community. stpetersbaycommunity.com

3 Comments

1/26/2019 09:57:18 pm

Yesterday I keep babbling about natural anti depressants because I have been a strong advocate of it. I know some people who have killed themselves and I am 100% sure prescription drugs are the culprit. Yet here I am struggling with battles which I created myself and I am so close to trying those medications myself. I know I shouldn't let them win. I need to feel better but I have no idea how. I tried everything on my list. I guess there is no real solution than a real solution to any of the things that bother us. Even nature can't be enjoyed if there is some problem waiting for you when you get back home.

Reply

2/19/2020 11:42:13 pm

We are looking into the possibilities, for example, if the cameras with back screen can record quality videos and take pictures.

Reply

Anna Lewis

3/26/2021 12:18:05 pm

Although I no longer live on PEI, I grew up on a farm on Cable Head East Road and I still remember the stories of the Turret Bell that my parents told me. I always thought the Turret Bell was destroyed. I was happy to read she got repaired and sailed again to experience more great adventures. I love this article. Thank you.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed