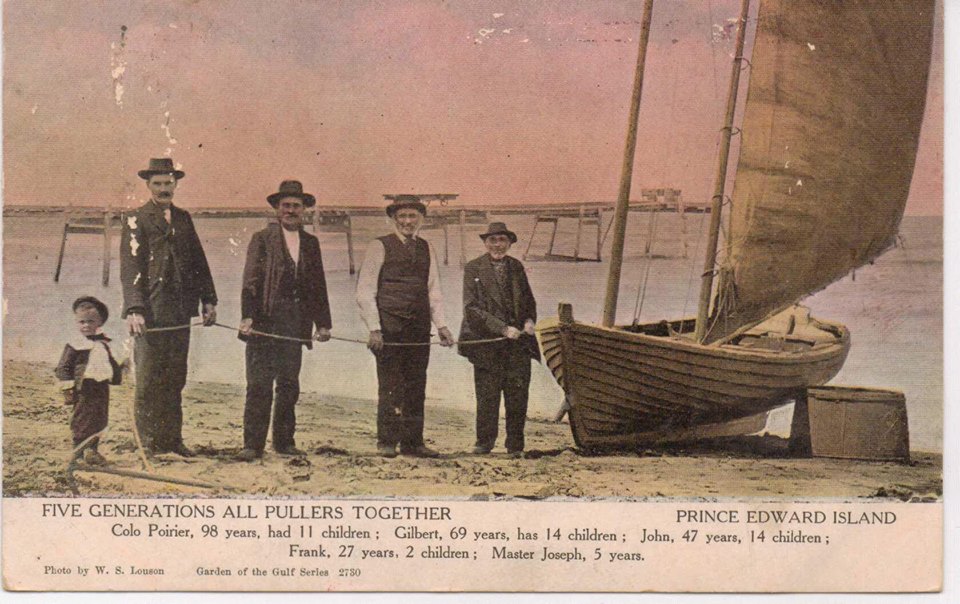

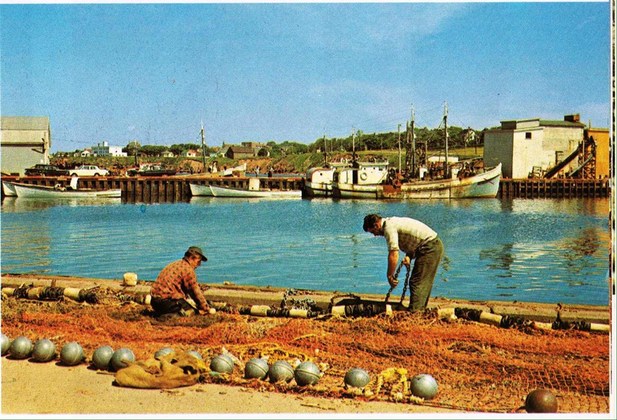

A unique sight, even by today's standards: five generations of Island fishermen. A unique sight, even by today's standards: five generations of Island fishermen. It has been said of the lobster industry that “nothing — not the fall of governments or birth of kings or the discovery of new galaxies — is of so much importance and interest as the question of whether the boats will be able to go out today, and whether the lobsters will be crawling”[1]. This sentiment, it seems, remains as true today as ever before. And while some things, such as the ever pertinent questions of the winds and the waves remaining static, there is much in the lobster industry that has changed over the past 300 years, from the fisheries’ humble beginnings to its indelible place in our Island culture today. Early Days In the earliest days of the industry, lobster were eaten out of necessity, not out of desire, as they were readily available in numbers of great abundance. They would be gathered, as needed, along the shore, or found in tidal pools when the tide receded. Lobsters were much more plentiful then, and in dire times they provided the sustenance needed for a family to survive.  One of the Island's earliest lobster boats. These were all made by hand. One of the Island's earliest lobster boats. These were all made by hand. The availability of lobster was attested to in one of the earliest known references to Atlantic lobster, noted by a Captain Leigh in 1597 as he sailed near Cape Breton, where in a letter he wrote that “there are the greatest multitude of lobsters that ever we heard of; for we caught at one haul with a little draw net [more than] 140.[2]" This could scarcely be considered industry, though, and it wasn’t until around 1850 that lobster traps as we would know them today began to appear[3]. It was in these days that men finally ventured out to the sea in order to reign in the humble lobster, taking to the water in small, handcrafted boats which the men would use well within the sight of shore. This was backbreaking work, navigating the waters under only the power of a set of oars or a small sail, but it was sufficient to bring home enough to get by on. A "Poor Man's Food" The prevalence of lobster in the hands of the working poor, coupled with its admittedly alien features, soon gave rise to the notion, on the Island and abroad, that lobster was something of a “poor man’s food”[4]. This is a notion that is well attested to, even to this day, in Island parlance, as well as in written reference. It even became common practice to serve tenants and employees lobster so frequently that rules were put into place specifying that they could not be forced to eat lobster more than three times per week[5]. Such rules were not to be implemented when it came to the preparation of lunches by school aged children, and meager mothers were often forced to prepare lobster sandwiches for the school day. There were those students whose pride was stronger than their hunger, who would scrape the lobster off on the way to school, and instead pretend that they had a butter sandwich instead. A butter sandwich is no regal meal either, and so for it to be considered loftier than one of lobster is quite telling.  The Basin Head lobster factory, as it appeared in the 1940s. Known as "The Cannery", this factory is still in place today, and hosts an ice-cream shop and fisheries museum. The Basin Head lobster factory, as it appeared in the 1940s. Known as "The Cannery", this factory is still in place today, and hosts an ice-cream shop and fisheries museum. The Cannery Is King It wasn’t long after this time that a proper market was established when lobster canning factories began to spring up around the Island. The invention of better canning and sealing technologies meant that now lobster could be stored and preserved for a much longer amount of time, allowing the seafood product to be shipped greater distances without spoiling. This opened up a lucrative market, both in the United States and Europe, where millions of people were willing to splurge on what was increasingly coming to be considered a delicacy, considering its exotic sea-side origin. Factories were built at Cow River, Basin Head, Fortune, Sheep Pond, and North Lake, just to name a few. Steadily Onward With the dawn of a new century came improved methods of boat construction, which permitted the fishermen to venture ever further onto the water, resulting in increased catches and yields. It was this time, too, that saw the establishment of a fisherman’s territory, something which has been honored, not by any outside legality, but by custom and tradition alone, to this very day. The fishing limits, zones, and boundaries which were established in those early days of lobster fishing were informal, and were done so only out of best practice. However, as the water became further populated by more and more men entering the industry, those previously established locales remained the right of the earlier owner to fish. When a fishing license was handed down from one generation to another, so too were the rights to fish in a given area, a tradition which has continued.  Fixing nets in Souris, ca. 1960. At this time the boats are transitioning from handmade to manufactured. Fixing nets in Souris, ca. 1960. At this time the boats are transitioning from handmade to manufactured. And so, to return to the present day, much remains the same. On the daily fisherman set out at dawn or early to haul in their traps, the design of which has changed very little since their introduction. Boats are now made commercially, however traps are still built by hand during the long winter months, as fishermen await “setting day”, which is typically around the end of April. Lobster are still hauled ashore at the harbor, where fish buyers wait to purchase the catch and ship it off to market. And behind it all remains the ever-present connection to the sea, the Island, to the way of life which has kept food on the table for generations of Island families. It is an industry steeped in history and tradition; an industry that will surely continue to be an integral part of the Island way of life for generations to come. To learn more about lobster fishing and the lobster industry, to experience the catch of the day being hauled into the harbor, and to discover life at one of the Island’s liveliest harbours, check out Red Rock’s daily Harbour History tour. References: [1] Bidgood, Jess. “A Fisherman Tries Farming”. New York Times. 10 October 2017. [2] Johnston, J.B. “The Early Days of the Lobster Fishery in Atlantic Canada”. Canadian Parks Service. 1991. [3] “Lobstering History”. Gulf of Maine Research Institute. 24 February 2012. [4] Johnston, J.B. “The Early Days of the Lobster Fishery in Atlantic Canada”. Canadian Parks Service. 1991. [5] “Lobstering History”. Gulf of Maine Research Institute. 24 February 2012.

3 Comments

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed