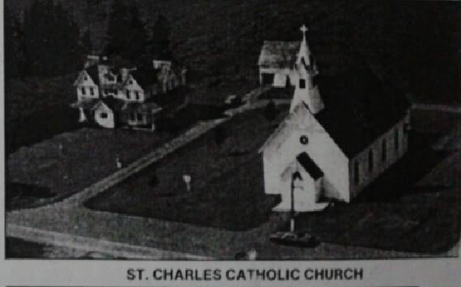

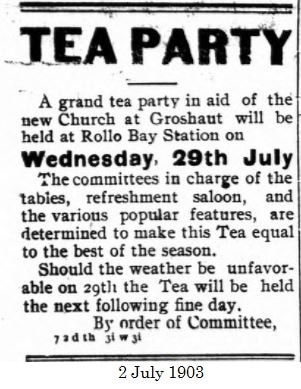

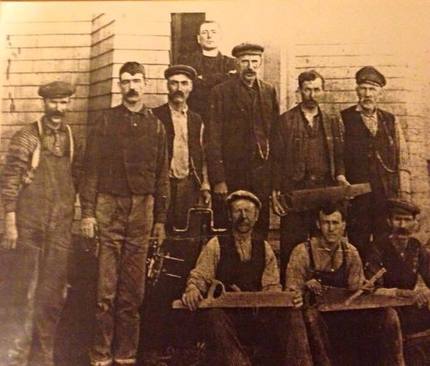

The only purported photo of the picnic at Groshaut known to exist. Courtesy University of Maine archives. The only purported photo of the picnic at Groshaut known to exist. Courtesy University of Maine archives. The Picnic at Groshaut is now an almost forgotten part of our Island heritage, but its story still manages to live on in the memory of those locals who pass the tale down from one generation to the next. It was an event that, despite its genteel name, brought a mark of notoriety to an otherwise quiet area, for the Picnic at Groshaut marked one of the most raucous and uproarious days that the Eastern end of Prince Edward Island had ever witnessed. In fact, such a spectacle has never been since.  An old fashioned picnic in the King's County area. This one took place in Fortune. An old fashioned picnic in the King's County area. This one took place in Fortune. Picnics and Places There are many who would observe that little has changed on Prince Edward Island over the past hundred or so odd years. One can still find their way down a winding country road, and revel in the unspoiled scenery which seems to expel a certain sense of nostalgia, creating a warm and vibrant image in one’s mind of days gone by. It was a simpler time in many regards, punctuated by a strong connection to community and culture, a connection without which most would not have survived. And while many things on Prince Edward Island remain the same, some traditions do change. Nowadays, in our all too busy and often hectic life, we find entertainment behind our screens and devices. But, at the close of the nineteenth century, entertainment was an altogether different matter. It was a time when people sought, and found, entertainment and pastime in the company of others, and one of the most popular pastime’s in Island life back in those days were church picnics. As Rossiter explains, “it was customary at that time to have a picnic or tea parties” (3). Reminiscent of Anne Shirley’s visions of an ice-cream social, these church picnics were just as you would imagine: they offered games and activities for the children, food and drink for the adults, with song and dance for the entertainment of all (1). They were much heralded events, and those church picnics which had garnered a reputation for splendor were widely attended. Such was the case of the Picnic at Groshaut, which drew in crowds from as far away as Charlottetown. This alone is an impressive feat, given the miniscule nature of Groshaut itself. In fact, Groshaut (which, in Meacham’s 1880 atlas was spelled Grosheaut), is so small that in modern times has, quite literally, fallen off of the map. Small, yet undaunted, the people of Groshaut worked hard to construct a church of their own, and when it was built it was named St. Charles Catholic Church, and in 1925 the area was incorporated under the name St. Charles. While some farmers still use the name Groshaut as a reference point for their fields, it is a rare case to hear mention of the term Groshaut nowadays. Located on the present day Selkirk Road (Route 309), north of the Island Waste Management facility, the area is broadly referred to as Selkirk or St. Charles, depending upon who you ask, and there is no indication that Groshaut, as it were, ever existed.  An early aerial photo of St. Charles Catholic Church. An early aerial photo of St. Charles Catholic Church. Noblest Intentions Early records indicate that the people of Groshaut and the surrounding areas built their present day church in 1896. Although it is only a modest wooden structure, its outward appearance belies its inner intricacy. No expense was spared in the creation of the hardwood interior, something that still delights the eye to this day. Ornate carvings and wordwork decorate the entire space, all the way up to the very rafters, and it is noted that "a wood-worker from Charlottetown was hired to do the decorative carving on the pillars and the vaulted ceiling." These beautiful works of art were not cheap though, and so it was determined that a church picnic would be held, in order to raise money to assist in paying for the costs associated with the new church. Planning commenced in earnest, and attendance was expected to be large. The Groshaut area was already well known for their picnics, and their practice of placing advertisements in The Guardian, the Island’s provincial paper, served to draw in more picnickers. Furthermore, the St. Charles train station (which at this time was known as Rollo Bay station), was very close to Groshaut, and as a result it permitted people to arrive by train, a method which was both cost-effective and timely.  More Than Cider Inside Her The stage was set for a grand old fundraiser. Most notably, Father Walker, the new parish priest, had procured an order for several casks of sweet apple cider, a much loved local drink, and he had done so at a bargain rate (1). However, as it would soon prove to be the case, a mix up had taken place with the order and Father Walker had received, unwittingly, an entire shipment of alcoholic cider. And while even today we can imagine what havoc this could cause, it is imperative to point out how problematic this would have been in 1897 (1). As Ives notes, “strong drink was ritually forbidden” (1), and it would only be two years before Prince Edward Island began to move towards total prohibition. However, this didn’t mean that alcohol was an entirely foreign thing to those planning a picnic at Groshaut, for Ives also notes that alcohol “could usually be found, if not on the grounds at least conveniently close by off them” (1)  Some of the local area men, around the turn of the century, many of whom likely attended the Picnic at Groshaut. Some of the local area men, around the turn of the century, many of whom likely attended the Picnic at Groshaut. The Picnic at Groshaut The morning of the picnic dawned, and many men arrived to help with the set up and operations. It had rained the day before, and people were eager to get outside and enjoy themselves (3). However, the weather did not appear to be co-operating and it soon looked to be the case that the picnic would have to be called off. This news was disappointing, and so the men, before heading home for the day, decided to try a drink of the cider to cheer themselves up. Well, they certainly found it cheerful! No one is really sure about the details surrounding this pivotal point: did the men know what they were doing? It was entirely against decorum to be drunk in public, let alone at a church picnic, under the scrutinizing eyes of Father Walker. However, this cider would have offered a perfect excuse to do so. Whether the men knew or not, that fact is lost to time. The results of the actions, though, are not. As Rossiter writes, “when it was discovered that there had been a mistake in the order, and most people had been drinking hard cider… the picnic that summer day in 1897 took a turn for the worse” (3) One drink soon led to another, and it wasn’t long before that rainy field was filled with tipsy men who were looking for a good time. Words turned to boasts, boasts turned to shoves, and before too long the entire picnic was alight with curses, bravado, and blows. As Rossiter recalls, “there was a lot of scrapping, and it was a noisy, rough time… there had been a lot of strong drink going and mostly everybody was half full” (3). Things were certainly beyond Father Walker’s control at this point, and to make it worse, the rain had subsided and the sun had come out in full force. Word of the cancellation didn’t get very far, and the warmth of that sunny afternoon was too alluring to be missed. Despite Father Walker’s wishes, a crowd was descending upon the picnic grounds, with more expected on the afternoon train.  Far from the typical picnic scene, as pictured here, the Picnic at Groshaut was something altogether different. Far from the typical picnic scene, as pictured here, the Picnic at Groshaut was something altogether different. ‘Twas a Frolic None The Less What this crowd saw when they arrived on the grounds was the stuff of legend. Instead of the pastoral scene of picnickers and pleasantry, attendees were stunned to witness the muddy mess of the drunken men. It was a spectacle never before seen in Groshaut, but somehow, the crowd was undaunted and took to the celebration like none other. The picnic continued against all rules of decorum (2), and was such that never again was rivalled. Doyle writes that “there was scuffles through the crowd and the noise was rather loud” as people continued to arrive, and explains that even the “old men with foreheads bare threw their dusters in the air/ Wanting someone for to fight them at Groshaut” (1). The dancing was frenzied, the drink continued to flow, and there appeared to be nothing that Father Walker could do about it. On the contrary, it proved to be one of the most successful picnics that the church ever held. By the end of the day Father Walker was mortified, not only at the behavior of his parishioners, but at the fact that this was to be a two day event. There was no way he could permit such debauchery for a second day, and so “after it was all over and everyone had been sent home, he carefully and heavily watered what remained in the kegs, and the next day everything was sober and uneventful.”(1)  One of the old roads which led to Groshaut. One of the old roads which led to Groshaut. A Musical Legend The story of the Picnic at Groshaut was one retold time and time again, and it must be remembered that St. Charles church stands in such prominence as a result of the funds raised from this memorable day. However, like many events of the past, what really cemented the Picnic at Groshaut into the folk memory of the Island was its musical retelling by Lawrence Doyle, the “Farmer Poet of PEI” (3). Doyle was a man of many trades, and he lived his entire life in an old homestead on the Fortune Road (which is now known as the Main Road, Route 2), near Farmington. In the Meacham 1880 atlas he is listed as the postmaster for Farmington, and also worked variably as a sort of vet, a carpenter, and as an impromptu lawyer who prepared wills and deeds (3). Rossiter recounts that he even prepared bodies for funerals (3). He was a colorful man, but he is best remembered for his musical ability. He wrote countless famous folk songs and his song “The Picnic at Groshaut” is no exception. The lyrics detail the events described above using his usual wit and satirical view, but they serve also to give us a first-hand account of the event (albeit perhaps with some embellishment). The song remains popular to this day, and can be still heard in the kitchens of the Kings County from time to time. To listen to the song, or to view the lyrics, click here. All's Well That Ends Well Despite Father Walker’s disapproval, the Picnic at Groshaut proved to be memorable in more ways than one, and it must be noted that even Father Walker must have had some ability to laugh over it all, for church picnics were held subsequently for the next few years, well into the new century. And while there was no doubt a great crowd at the Picnic of Groshaut of 1898, there was no way that it could have lived up to its predecessor. As Rossiter concludes, “there were picnics held in Groshaut after 1897… but they weren’t always rowdy like this one” (3). Like our posts? Be sure to like and share on Red Rock Adventure Company on Facebook! References:

1. Ives, Edward D. Drive Dull Care Away: Folksongs From Prince Edward Island.Charlottetown, PEI: Institute of Island Studies, 1999, 177-180. Print. 2. Perlman, Ken. Couldn’t Have a Wedding Without the Fiddler: The Story of Traditional Fiddling on Prince Edward Island. University of Tennessee Press. 2015. Print. 3. Rossiter, Juanita. Gone to the Bay: A History of the St. Peter’s Fire District Area. 2000. Print.

17 Comments

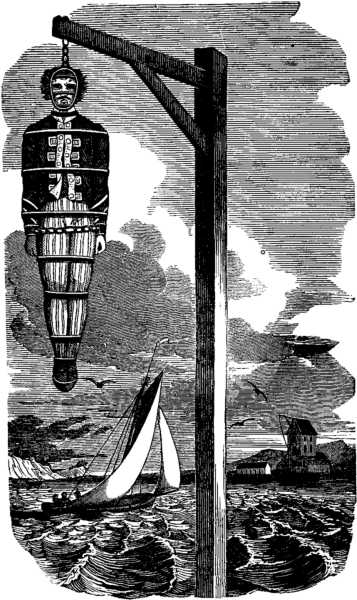

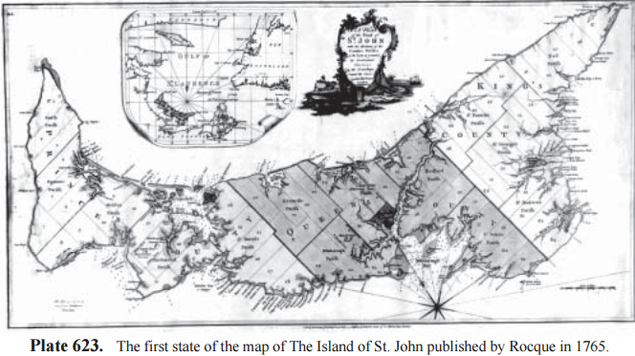

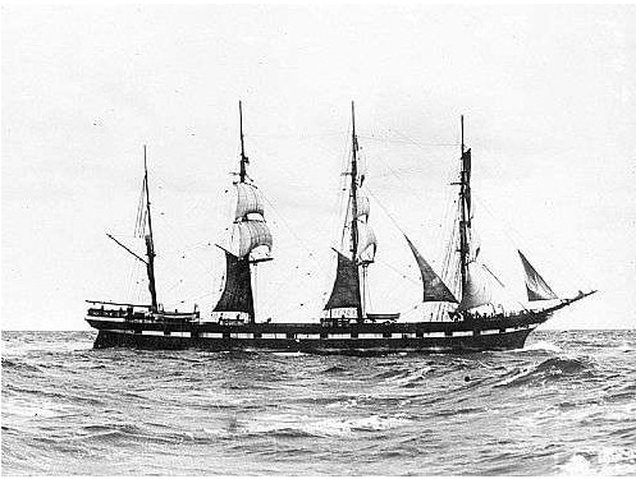

There was a time, back around the turn of the century, that Bay Fortune, Prince Edward Island, had taken on a life of its own, one distinctly different from the way it is today. Settlement was in full swing here, and the area was heralded both provincially and abroad as a paradise to be found. An actor’s colony, filled with some of the finest stock which the American theatre scene could produce, had taken root here, and for all intents and purposes it was a paradise (3). It was, and remains, a place of beauty; of locale of allure that proved all the more attractive for the mystery which maintained a firm grasp in the minds of locals and tourists alike, namely, that Bay Fortune was “made famous as the receptacle and hiding place of Captain Kidd’s stolen hoards” (1) These legends have persisted for time immemorial, but they gained popularity as they were rediscovered by those of the actor’s colony who summered here. For example, in the Prince Edward Island Magazine, dated December 1901, Charles Kent, one member of the colony, provides a detailed introduction to the subject, although he too expresses his incredulity surrounding the claims of Captain Kidd and his buried treasure (1). However, despite this apparent disbelief, the legend lives on, and can be traced through the pages of history in such a way so as to lead even the most doubting to at least question the possibility. And while it may seem to be an outlandish assertion, such claims are not entirely out of character for the Fortune area, which has a long history of relations with the dark and unexplained. Forerunners abound in the area; a wounded man made his death-bed will to be buried upon the cape (which he was), ghosts are known to haunt its dark woods, and even Charles Coghlan’s floating coffin found its way to Bay Fortune’s shores (3). In fact, this very site gained notoriety for Patrick Pearce’s infamous murder of Edward Abel, the namesake of the Cape itself (3). With that being said, it is no surprise that the persistent claim of buried treasure lingers to this day, and thus, we turn our attention backwards in time, in order to explore the mysterious history of Bay Fortune.  Portrait of Captain Kidd. Date unknown. Portrait of Captain Kidd. Date unknown. Who was Captain Kidd? Captain Kidd was perhaps one of the most infamous pirates of his time, and to this day his name is still synonymous with piracy on the high seas. Born in Scotland in 1645, his family emigrated to the United States when he was only a young man (4). There, amid rising tensions between England and France, Captain Kidd found employment working for the British government as a privateer – hired by European royals to protect British shipping interests at sea in the Caribbean, and furthermore to thwart French naval expansionism and trade. This line of work had in the past proven to be a lucrative industry, as it was well known that privateers were to gain the profits of any rival ship which was confiscated. His career as a privateer proved to be successful, and in 1696 he was commissioned to travel to the West Indies aboard the ship the Adventure Galley, under the funding of English Lord Bellomont, to attack French ships and pirate vessels there (4). Kidd’s endeavours in the West Indies were less than noteworthy, and amid illness and unrest aboard the Adventure Galley, Kidd quickly determined that a successful bounty would needed be if he were to avoid mutiny aboard his ship. It was then, as it seems, that Fate intervened, for as his ship rounded the tip of India, it encountered the Quedagh Merchant, a 500-ton Armenian ship carrying gold, silk, spices, and other riches, owned, in part, by the Indian Grand Moghul. The ship was poorly defended, and such an opportunity was to come only once in a lifetime (4). Decisively Captain Kidd ordered his men to assail the vessel, and in no time it was under Kidd’s control. Word of the capture of the Quedagh Merchant hurriedly reached England, as the ship had been under the direction of the East India Company. Condemnation came swiftly, and Captain Kidd was soon sought by English officials, wanted for the act of piracy.  An etching illustrating the hanging of Captain Kidd. An etching illustrating the hanging of Captain Kidd. This was of little consequence to Captain Kidd, who now patrolled the Indian and Atlantic oceans aboard the regal Merchant. The powerful ship yielded him greater fortunes as he made his way back to the Caribbean and up the eastern seaboard of North America. Alas, during a stop-over in Boston harbor, Captain Kidd was captured and shipped back to England. Once in Europe, Kidd’s trial was swift and merciless. Captain Kidd found no friend in Lord Bellomont, who would have had his own dealings in privateers scrutinized had he come to Kidd’s aid. As such, little defence was mounted, and Captain Kidd was found guilty of piracy and hanged on 23 May 1701. Moreover, to serve as a warning to other pirates, his body was hung in a cage over the river Thames, and left to rot for all to see (4).  An illustrated coin, drawn in reference to Kidd's treasure at Bay Fortune. An illustrated coin, drawn in reference to Kidd's treasure at Bay Fortune. Fortune's Treasure But what of his treasure? It seems that to this day history has neglected to account for the whereabouts of Captain Kidd’s treasure, and perhaps for good reason; as legend has it, Captain Kidd had anticipated such events, and had arranged to have all of the treasure buried before he was captured. Such a treasure would be vast: not only would it contain the aforementioned wealth of the Quedagh Merchant, but also the riches of any of the smaller vessels which he had assailed in his journey westward from India. This treasure would necessarily need to be hidden in a remote area, far from the prying eyes of other pirates, and moreso, from the government agencies which sought to thwart him. It is with these facts in mind that we then turn our attention to Bay Fortune, Prince Edward Island, for here in Fortune do we discover a long and colourful connection to Captain Kidd’s treasure, as rumor has it that his treasure is buried here. This is, of course, a sensational claim; however, it is not made without any evidence. In fact, one need only look as far as the name of the area itself as an indication of the treasure which may be buried there. The etymology of the Fortune area is thought to refer to the ship La Fortune, an English schooner weighing 40 tons which was brought to the area in 1754 by Le Sieur Laborde (5). This, however, is contradicted somewhat by Rayburn in Geographical Names of Prince Edward Island, as he indicates that "de la Rocque (seen below) shows Riviere a la Fortune in 1752", two years prior to this schooner. Given this, it is posited that the name may possibly mean "river of riches" (5).  And as if this weren’t enough to lead one’s mind towards the connection with Captain Kidd, Reginald Carrington Short, one of the famous members of C. P. Flockton’s acting company who summered in Bay Fortune and whose autobiography details the subject matter extensively, suggests a direct connection between Captain Kidd and the naming of Bay Fortune, writing that “a strong belief persisted among the natives [Islanders] that somewhere on the Cape…Captain Kidd, had buried his treasure. This fact may have been responsible for the name Fortune Bay on which the Cape itself was situated.” (2). Given the inconsistency in naming as indicated above, perhaps there is some validity to Short’s claim.  Abel's Cape, as it appeared in the Island Magazine. RC Tuck, artist. Abel's Cape, as it appeared in the Island Magazine. RC Tuck, artist.  Digging for Kidd's Treasure, as described by Bim in Short's Autobiography. The Island Magazine. Digging for Kidd's Treasure, as described by Bim in Short's Autobiography. The Island Magazine. In Search of Gold Short goes further, citing various local peoples who indicate to him that numerous attempts have been made to unearth the treasure (2). Kent too informs us that still it is visited by mystics and those with divining rods, all of them prompted by dreams to dig for Kidd’s gold, and that at the time of his writing there remained “Many holes proving how firm is the belief that the treasure is buried here”(1). Countless attempts have been made to claim the treasure, with one of the most infamous incidents relating to the ‘Boys from Boston’, which transpired around the turn of the century. As Short explains, one of the old locals, a Mr. Abimelech “Bim” Burke, was confronted by two men from Boston who had travelled all that way in search of the treasure (2). These men asked Bim if he knew of Abel’s Cape, and, when he answered in the affirmative, asked if he would help to guide them there. They offered him a bit of money and some ‘Boston ‘shine’, and Bim agreed to lead them. He informed them, however, that “it ain’t no use diggin’ for treasure ‘ceptin at midnight; anyone’ll tell ya that” (2) And so the night went on, and the shine went down, as the men waited until midnight. They had a map, procured somehow in Boston, and as it was a terribly dark night they brought with them a lantern. So as the midnight hour neared, the unlikely trio headed towards the cape, but even the lamplight was little match for the persistent darkness, and as it was they were several hours before they landed upon the precise spot to dig. The search continued for some time, to no avail, until suddenly the clouds parted and the moon shone bright, as if guided by some unseen force. Bim then recounts that in the moonlight they suddenly saw the appearance of a regal ship (2). From the ship was seen to disembark a small rowboat, and as Bim and the others looked on, they spied inside the boat “the worst looking lot you ever seen… handkerchiefs over their heads, belts full o’ knives and pistols.” There was no doubt among the treasure-hunters that before them was the apparition of Captain Kidd himself. As Bim tells it, they were back to his place “like the devil hisself was after us. Mebbe he was. Seems like I smelled brimstone” (2) As for the boys from Boston, they were out the door at the crack of crow and caught the train from Bear River, bound for a return trip to Boston. They left in such a hurry, Bim notes, that they left their prospecting tools behind (2). Given the above, it is no surprise that the stories best remembered about the treasure are those with a comical conclusion, for another one is often told of the search for the treasure, wherein the 1920s a young man from Souris ventured out to try his luck in finding it (6). However, some local boys caught wind of this development and before he could arrive they quickly buried a metal bucket full of stones in the area. That night, again by moonlight, the young man and his friends prowled for the treasure, and were focused upon digging when one of their shovels struck something metallic, shattering the silent night (6). Excitedly they pulled forth from the ground the source of the sound, only to discover that they had been fooled, and that their treasure was nothing but a bucket of rocks. Nothing else came of their expedition, save for the laughs of the boys who eagerly retold the story in the days to come (6).  Bay Fortune Shore, as it appeared in 1901. Prince Edward Island Magazine. Bay Fortune Shore, as it appeared in 1901. Prince Edward Island Magazine. The Search Continues Stories such as the ones above abound in the collective memory and folklore of the local people, and to this day the evidence of these digs, the pitted pockmarks and potholes of explorers from days-gone-by, continue to dot the landscape of the cape (6). A worn and well beaten trail winds its way from Fortune Back Beach up into the cape, indicative of the persistent memory of Captain Kidd’s treasure. Whatever the truth, whether it be pirate’s gold or merely fool’s gold, Bay Fortune continues to offer the allure of something more than meets the eye, and it is certain to continue to do so, for many years to come. As Kent notes, while many still search for the treasure, “they are always unsuccessful, and are usually scared away by the ghosts of Kidd and his crew,” something he too fell victim of in years gone by (1). He writes that “for weeks I have searched and delved in the sand, but all to no purpose save the amusement of the Islanders,” a sentiment all too common in the search for Kidd’s gold (1). And so, he concludes, that despite the endless onslaught of “moonlight diggings” which the passage of time has brought forth unto the area, none of them shall ever succeed, for “Kidd’s spirit knows how to protect it” (1) But as to the treasure itself, Kent is more than confident: “that it is buried here is now an undisputed fact” (1). Want to learn more, or keep up to date on our latest postings? Follow us on facebook! To explore more of the history of eastern Prince Edward Island, visit us at the Red Rock Adventure Company to book your own personal guided bicycle tour. References: 1. Kent, Charles. Ed. Irwin, Archibald. "Kidd's Treasure" The Prince Edward Island Magazine. 1901. Print. 2. Short, Reginald Carrington. Ed. Hornby, Jim. "The C.P. Flockton Comedy Company" The Island Magazine. 1982. Print. 3. Townshend, Adele. "Drama at Abel's Cape" The Island Magazine. 1979. Print. 4. William Kidd, Pirate. Biography. Biography.com. 22 February 2017. 5. Sourispedia. "Fortune, Prince Edward Island." 22 February 2017. 6. Eastern Kings. "Captain Kidd's Treasure" Island Narratives Program. 22 February 2017. Note: This is part two of our ongoing series documenting some of the ships which were wrecked during the November Gale of 1906. For our first post, click here. A Worldly Crew Just as was the case with the Turret Bell, the Sovinto was a cargo ship which had seen service over its lifetime delivering goods to all corners of the globe. Unlike the Turret Bell, however, the Sovinto was a four-masted barque, renowned as a sailing ship. It had been built by Barclay, Curle & Co, Ltd., of Whiteinch, Glasgow, and was owned by a Finnish owner at the time of the wreck. It measured 61m in length, and weighed 1600 ton. It was commanded by a Captain E.K. Wiglund, and boasted a Scandanavian crew of twenty-one men. These men were natives of Norway, Sweden and Russia, and only the Captain alone was able to speak English. The Sovinto had sailed out of Campbellton, New Brunswick on the morning of Sunday, 4 November 1906 carrying a load of a million and a half feet of lumber, and was headed for Australia. The November Gale Readers familiar with the November Gale of 1906 will recall that this storm was one unprecedented in previous maritime history. It was a storm that could not have been predicted, for The Guardian of 5 November 1906 wrote that "even weather vanes were deceived. The barometer gave no warning; the weather possibilities conveyed no hint of more storms..." Despite this, the November Gale raged on for almost two weeks, and dumped eight inches of rain upon the area. Even as the Sovinto set sail there was no indication of foul weather ahead of them, the skies being fair in Campbellton, and it was not until Sunday evening that they encountered heavy seas and strong north winds. These winds developed without warning and with haste, and by the time the Captain and crew realized that they had sailed into the tempest, it was too late for them to resist it. Gale force winds ravaged the helpless vessel, and as the winds increased, the jib and foretopmasts were torn to pieces; the upper topsail was blown away, and the starboard anchor broke loose. Adding to their difficulties, their cargo had shifted to the starboard side, causing a great pitch to the deck. Without delay the Captain ordered each man a life buoy for his own safety. By Monday morning Captain Wiglund had shifted the course to south-west in hopes of riding the storm down wind. They maintained this position until about 3PM, by which time the crew had finally gotten the anchor up and had cleared much of the deck load. They then turned the ship onto a starboard tack to avoid the Magdalen Islands (les Iles de la Madeleines).  The Sovinto, run aground. The Sovinto, run aground. Panic at Priest Pond On the evening of Tuesday, November 6th, the lookout reported waves breaking on the leeward side, indicating shallow water. The man on the sounding line reported only seven fathoms (approximately 13m). The Captain then gave the orders to drop both anchors, but the order came too late as the ship ran heavily aground on the rocky bottom of Carews Reef off Priest Pond before the starboard anchor could be dropped. The ship was lodged about 180m from shore. As the ship ran aground, one sailor, named Gerwick, was tossed into the sea and was cast adrift. As is detailed in the Historical Sketch of Eastern Kings, by some miracle he was able to reach the shore in the inky darkness, in the face of the abundance of hazardous wreckage which presented itself in the roiling waters. Despite the late hour he scrambled up the cliff side and raced to the only light in sight, the still burning lantern in a distant window. This, it would turn out, was the home of a Mr. Joe Rose. Gerwick pounded fiercely upon the door of the home, but when Mr. Rose came to the door he could not understand who this man was or from whence he had come, for he spoke no English. It was only through sheer repetition of the word “barque”, which is an English loan-word for a type of ship, that he was finally able to convey the tragedy of the wreck.  The wreck site today. The wreck site today. A Desperate Dawn When the ship struck the reef, it was lodged broadside and perpendicular from the shore, making it impossible to launch the lifeboats. Large waves were washing over the deck and the rigging was coming loose. Captain Wiglund called for the crew to be assembled in the starboard cabin, which was still dry and above water. Seventeen men were assembled, leaving four missing; one being Gerwick. The other three, one of them named Kumlander, were trapped on the bow of the ship and unable to reach the cabin. The storm continued to rage, and sometime during the night the ship broke in two, spilling the entire cargo of lumber into the waves. By daylight on Wednesday the shore had been littered with lumber and debris from the wreck, and the wind and waves were so powerful that they sprayed up and over the cliffsides of the shore. A group of onlookers and rescuers had gathered on the shore, and despite the spray and mist, the men on shore were able to see the men still remaining on the wreck, clinging to the deck. A sailor washed ashore that morning still wearing his life buoy. He was badly mangled by the lumber being tossed about in the waves, but still alive. Attempted Rescue Shortly after, the men still remaining on the wreck attempted to launch the life boat, only to have it fill with water within minutes. Seven men drowned as a result; one was only twenty feet from shore when he was swept under, and another was thrown against a flat rock and then pulled under before help could reach him. Seven made it to shore, despite being badly injured. Two others were washed back onto the wreck. One other was swept onto the bow of the ship, left to join his three comrades who had been trapped there since Tuesday night. By Thursday morning, November 9th, only three men remained on the ship; the two souls who had been washed back onto the wreck after the failed life boat attempt, and the twenty-two year old named Kumlander, the lone man who remained clinging to the bow. His three companions had been swept overboard during the night. News of the wreck had spread overnight, and the Stanley, a steamer from Souris had been given order to come to the rescue. Daylight found a large crowd of spectators and reporters from as far away as Charlottetown, all of whom braced themselves against the howling wind and surf to watch the spectacle unfolding before them. A crowd had formed on the shore as well, consisting of local fisherman and those who had been pulled from previous wrecks (The Olga and The Orpheus) earlier in the week. These men knew the sea well, yet were powerless to help in the surging waters. All hopeful eyes looked eastward for the arrival of the Stanley, but due to treacherous currents and winds, she never arrived.  A portion of the Sovinto's crew. Kumlander is holding the life buoy, Captain Wiglund stands in the center. A portion of the Sovinto's crew. Kumlander is holding the life buoy, Captain Wiglund stands in the center. A Heroic Effort It was then that two young fisherman, Duncan Campbell and Austin Grady, both of East Baltic, noticed that the hull of the ship had shifted sideways somewhat, enough to break the force of the waves, if only slightly. Choosing to capitalize on this opportunity, they decided to attempt a rescue using a dory. They launched the small boat into the water, and from the outset struggled to keep the bow headed into the water. Eventually they were able to reach the hull despite an easterly current. The two men clinging to the hull were rescued, and repeated attempts were made to save Kumlander by throwing him ropes. Numerous attempts failed, and the risk was too great to leave the small shelter of the hull. To Kumlander's certain despair, they were forced to head back to shore, leaving him as the last remaining man on the wreck. By Thursday evening, Kumlander had been without rest, food or water for over forty eight hours. He was desperate now, and rather than spend another night clinging to the bow, he took hold of a nearby plank and jumped into the churning sea. He was caught in the current and tossed around the hull before being swept off in a large wave towards the rocky shore. Those on the shore chased after him with ropes, and he was luckily able to catch one. He was briefly dashed across the rocks as his rescuers pulled him ashore, but finally the ordeal was over.  Austin Grady and Duncan Campbell, as they appeared in the Daily Patriot, November 29, 1906. Austin Grady and Duncan Campbell, as they appeared in the Daily Patriot, November 29, 1906. The Aftermath Of the twenty-one men aboard the ship, twelve lost their lives. Those who survived were taken to local homes to recover, although some later died of tuberculosis. Their burials were paid for by Lloyd's of London, who were the insurers of the vessel. Eight of the bodies were buried in the graveyard at St. Columba parish. As the storm subsided and the tide receded, children played upon the wreck, and rounds of cheese floated ashore. Debris from the wreck was used by locals to build and furnish their homes, and some of these home still remain today. Both Austin Grady and Duncan Campbell received a sum of money from the Patriot, and were later presented with the Carnegie Medal of Bravery for their extraordinary heroism. Today, over 100 years later, the wreck is still visible at low tide, and remnants of the wreckage can still be found. The memory of the Wreck of the Sovinto continues to live on in local folklore, and the wrecksite itself has become a popular spot for Island divers. To discover more about the Island's hidden history, from shipwrecks and rum-runners, wishing wells and ghost stories, visit the Red Rock Adventure Company home page, and learn about all the touring opportunities which we offer. This project is made possible through a partnership with the Red Rock Adventure Company and theSourispedia Project. Click here to read about The Wreck of the Sovinto with complete intext citations.

Townshend, Adele. "The Wreck of the SOVINTO" The Island Magazine 1978: 36-39. Print. Watson, Julie V. Shipwrecks and Seafaring Tales of Prince Edward Island. Hounslow Press: Toronto, 1994. Wrecksite. "SV Sovinto (+1906)" The 'Wrecksite. Oct 1 2012. Web. Feb 8 2013. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed