|

1. Souris Originally named Havre a Souris, which translates to “Mouse Harbour”. Later shortened to Souris, the area got this name after numerous plagues of mice infestations, with one reportedly being so prolific that mice were seen to tumble over the cliffs and into the harbour, to such an extent that passing ships had difficulty navigating the waters. Other names which did not stick were Colville and Red Cliffs. 2. Red House Named for a house built by Edward Abell, the infamous land agent for the area. It was painted red by a Mr. Heal, a notorious coroner who had condemned a man who had committed suicide to be buried opposite the house with a stake driven through his body. The Bay Fortune post office was at Red House until 1880. 3. New Zealand This name was given in jest 1858 because settlers were going to this place at the same time as some people were departing from Charlottetown for New Zealand with much fanfare. 4. Bear River There are two stories which seek to explain the origin of this name, both of which follow the same theme. One is from a time when it was known to foster many bears along the river, and the other, more memorably, is from when one of the early settlers, Roderick MacDonald, fought and killed a large bear with his bare hands. 5. Fortune The etymology of the Fortune area is thought to refer to the ship La Fortune, an English schooner weighing 40 tons which was brought to the area in 1754 by Le Sieur Laborde. This, however, is contradicted somewhat by Rayburn in Geographical Names of Prince Edward Island, as he indicates that "de la Rocque shows Riviere a la Fortune in 1752", two years prior to this schooner. Given this, it is posited that the name may possibly mean "river of riches", and may be a reference to the long lost treasure of Captain Kidd. 6. Chepstow Named after a settler from Chepstow, Monmouth, Wales. While the name today refers most often to the community proper, at different times Chepstow Point was used. So too was Chepstow Cove, which is located at the bottom of present day MacAulay’s Road, below Steele’s Lane. Chepstow was also once home to a post office and school. 7. Rollo Bay Previously Rollo's Bay or Lord Rollo's Bay, is named after Andrew Rollo, 5th Lord Rollo, who was a Scottish army commander in Canada and Dominica during the Seven Years' War, who led the British land forces in the Capture of Dominica on June 6, 1761. Earlier names were Havre a Mathieu and Anse-a-Matieu. These were after Turin Mathieu , who had a family of ten near East Point in 1752. Lower Rollo Bay, which is today considered to be anything along the Lower Rollo Bay road, was also known as Rollo Bay East, named after the Rollo Bay East Post Office which operated from 1888 to 1904. When the name of the post office was changed in 1904 the postmaster reported that "Lower Rollo Bay is done way with, belongs to ancient history, an anachronism so to speak". Contrary to the postmaster’s claims, the old name still thrives long after Rollo Bay East has disappeared. 8. Naufrage The name derives from the French word for shipwreck, and stems from the numerous shipwrecks which occurred as early as 1719 that brought the first European population to the area. Many of these settlers remained in the area, and are ancestors of today’s population, while some ventured west and formed the early community of St. Peter’s Bay. 9. St. Charles Named after St. Charles Borromeo, who was a prominent member of the church during the 1500s, and who was responsible for significant reforms in the Catholic Church, including the founding of seminaries for the education of priests. Prior to 1896 the area was known as either Groshaut, New Acadia, or Rollo Bay Station. However, with the construction of the church, the area came to be known as St. Charles. The St. Charles Road was known as the Bourke’s Road until around the time it was paved, when the name was changed. 10. Rock Barra This name is perhaps a little bit tongue-in-cheek. It was named for a rock that stood offshore, now washed away, that reminded one of the early settlers of the Island of Rock Barra in the Hebrides. Furthermore, tradition has it that a first settler, Mclsaac, exclaimed to others that "you might as well be on the rock of Barra" in reference to the barrenness of the land, something which he had hoped to escape by moving here. 11. Black Pond Named for the dark shadow cast by surrounding woods, something which is still apparent to this day. Early Scottish settlers called it Loch Dhu meaning "black lake", a name which many remember from the Loch Dhu Haven campground. 12. Bothwell Named by area resident Joseph McVean who was the one to name the Post Office, from which the area took its name. He chose Bothwell from the situation of "both" himself and his father living "well" side by side. Named around 1863. 13. Gowan Brae Formerly known as "New Bristol". Probably named for John Macgowan, early sheriff of Kings County and mill operator on Souris River The name also suggests "mountain daisy" and "hill" in Scottish. It was a school district in 1865, and had a post office from ca. 1886-1913. 14. Glencorradale Named after a resident of the area, a Mr. Haney of Souris Line Road, rose in opposition to an oppressive landlord with the support of his neighbours. Upon hearing about this the government sent soldiers to restore calm, and the uprisers took to the area of present day Glencorradale to hide. This event recalled in the minds of the uprisers the time in which Prince Charles hid at Glen Caradel on the Isle of Skye after his defeat at Culloden. Noting the similarities, settlers to the area from Inverness, Scotland in 1846 chose the name Glencorradale for the locality 15. Cable Head Said to be named for a piece of hemp cable found on the shore, evidently from a vessel. The first settlers called the place Ceann Cable (from the Gaelic "cable end" or "cable head"). 16. Hermanville Named for Herman McDonald, first settler (circa 1850) and postmaster, who was still living in 1905. Known also for its post office, and for the Hermanville Hotel located in the post office. Other names for this area were Black Brook, Black Bush, and Milton. 17. Monticello Records indicate that it was possibly named for the home of Thomas Jefferson in Virginia. Formerly known as Big Marsh and Big Cape. 18. Campbell’s Cove Named for Angus Campbell, resident there when the area was surveyed in 1808. Home to a post office from 1896-1913. Campbells Point, adjacent to the cove, may have been the first part of PEI sighted by Jacques Cartier in 1534. 19. Elmira Named by George B. McEachern in 1872 for Elmira, New York. It was selected for its euphony. Formerly called Portage because it was on the route from North Lake to South Lake. 20. Priest Pond This name has been in use since at least as early as 1832. It is suggested that it was named for Bishop MacEachern. Earlier records provide the name as Railing Bridge. 21. New Harmony Possibly derived from the area of Harmony Junction, where farmers of French, Scottish, Irish and English nationalities had settled and presumably lived amicably. If you liked this article, or wish to learn more, please check us out on Facebook and give us a like.

3 Comments

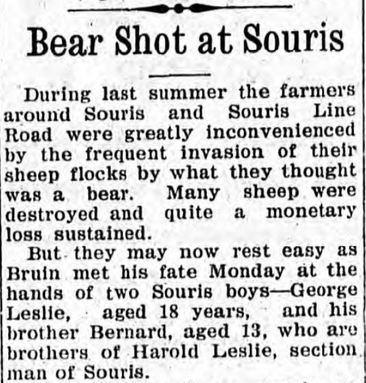

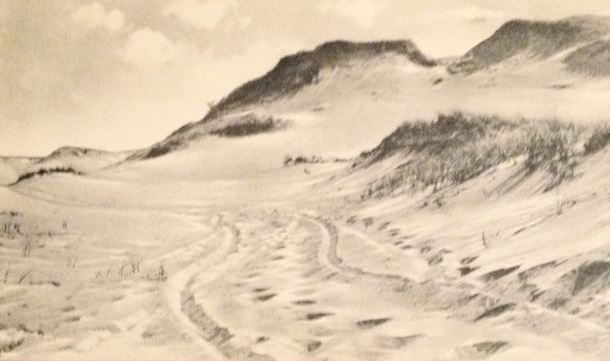

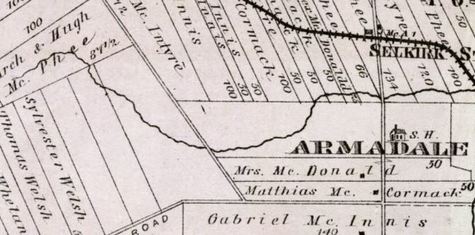

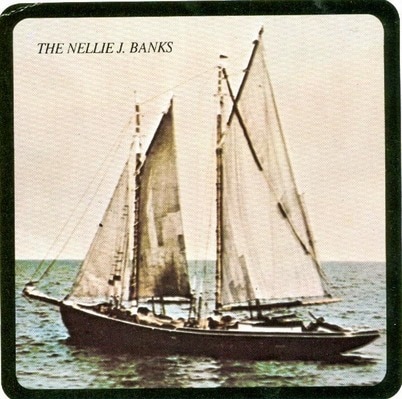

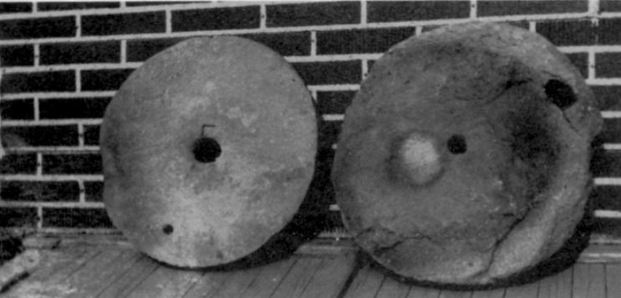

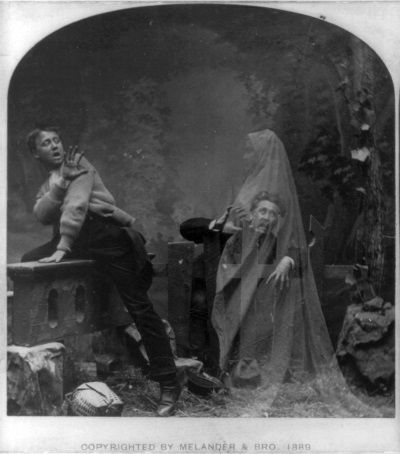

This article is the second in a series which continues to explore the rich history and heritage of Eastern Prince Edward Island. It is our hope that these stories provide you with a taste of what our cultural tours have to offer. To read an earlier installment of stories, click here.  To spot a bear in the woods was a fearsome sight indeed. 1930s post card. To spot a bear in the woods was a fearsome sight indeed. 1930s post card. The Last Great Bear Island history is rife with stories of bears, such that they almost border on legend. An ever present danger in the lives of early Island settlers, stories and fears of bears permeated the minds of these people, and even the sighting of a bear was enough to set the hearts and minds of Islanders on edge. At Norris Pond, near Souris, it is remembered that a bear once attacked a man walking home from the pond. The bear pounced upon the man, who was taken by surprise and caught completely off guard. He had no weapon with which to defend himself, and so in desperation he drove his arm down the bear’s throat and pulled out his organs, thus killing him. Another story from Red Point relates the untimely death of a bull at the hands of a bear. The bear, seeing the bull alone in the field, attacked it in a rage, climbing upon the poor creature. The bull though was not to go down without a fight. It carried the bear upon its back as it ran wildly towards the farmyard, and it was later, after the bear had proven victorious, that the farmer could see the desperate claw marks of the bear against the trees as it struggled to keep hold of the raging bull (4). And while the entire Island encountered their fair share of bears over the years, one would not be amiss to suggest that Eastern Prince Edward Island shared a particular connection to the bruin lot. In fact, it had been reported in The Guardian, as early as 1862, that "bears are becoming very numerous and exceedingly troublesome east of Souris.”  Islanders have long been intrigued by power and majesty of the bear. This "dancing bear", chained to its owners, appeared in Charlottetown in 1890s. PARO PEI Photo. Islanders have long been intrigued by power and majesty of the bear. This "dancing bear", chained to its owners, appeared in Charlottetown in 1890s. PARO PEI Photo. One need only look at the places which “bear” the name of the fearsome creature to understand what role they played in the pioneer psyche. Basin Head was once named Bear Harbour (4), as was Black Pond (Loch Dhu), while today’s Little Harbour beach had a unique stoney outcropping called Bear Rock. These names have largely disappeared, save for Bear River, which retains its reference to its grizzly past. The place boasts a dual claim to the animal; both from a time when it was known to foster many bears along the river, and more memorably, when one of the early settlers, Roderick MacDonald, fought and killed a large bear with his bare hands. (5) But most notorious of all in the Souris area is the story of the last great bear, a story which is known across the Island. According to Hornby, the last bear to have been killed on Prince Edward Island was killed on 7 February 1927. It was shot on the Souris Line Road by George and Bernard Leslie, who were 16 and 18 at the time, respectively. The event was reported on as the headline for the Evening Patriot on 8 February 1927 (6), and in The Guardian the next morning. It all began when the boys noticed the tracks of a bear crossing the north end of Souris Line Road, heading east. There had a been a spring thaw, and the boys knew that a bear would be active in that sort of weather. They didn’t tell their father about the sighting, saying that “he’d ruin the whole thing on us; he’d have to come”(6). Instead, they waited until the next day, until their father had left for Souris. With him gone, the hunt was on.  Taken from The Guardian. 9 February 1927. Taken from The Guardian. 9 February 1927. They tracked the bear all through morning, and it wasn’t until about one o’clock in the afternoon that they found it. It was risky work, following the trail of a wild bear, as it could have appeared from the thickets at any time. Doggedly the boys pursued their target, until at last, through the undergrowth, they spotted the animal. To their surprise, it was asleep. The boys held the perfect vantage point from the thickets, and George made the first move. He fired his shotgun from a distance of about 15 feet, striking the bear in the hip. The next shot caught it in the side of the neck. The bear sprang onto its hind legs, bellowing in a rage, but the boys didn’t retreat. The bear was clearly injured, and it soon fell to the ground in weakness. George stepped closer to his prize and took one more shot at it. Gunfire rang out, the clearing fell silent, and the Island's last great bear was dead. The carcass weighed over 400 pounds, and was skinned on the spot by the two boys. It was later boiled for its grease, and the grease was sent to England. For the grease they received $14, a considerable sum for two young boys at the time.  Greenwich was once a prominent farming locale. Greenwich was once a prominent farming locale. The Shifting Sands It seems fitting to include an entry about Greenwich National Park, as for the 2017 season all National Parks are open free to the public to celebrate Canada’s 150th birthday. Greenwich has a long and colorful history, dating all the way back to the Mi’Kmaq who fished off of its shores, and was a home to the earliest French settlers who migrated there from their shipwreck at Naufrage. For many years, before it was designated a National Park, the land around Greenwich was even farmed by locals in the area. Many changes have taken place at Greenwich throughout this time, but one thing that has always remained constant is the shifting sand dunes which dominate the area. In the years surrounding the turn of the twentieth century, the Greenwich sand dunes were as imposing as ever. In those days they were known as “the Commons”, and were fenced in entirely (1). Within the Commons all of the local farmers’ animals were set to pasture, and they would not need to be collected until the fall when the cool weather set it. Each animal was marked with the farmer’s specific brand, so that the animal could be distinguished (1). The Commons, it seems, was little good for much else, as any Islander who has lived near the shore can tell you. The sand is just too unpredictable. Take for example the flow of Cow River, which can, on the nightly, reset its course across the sands and in the morning appear as a new river entirely. Or, consider the open run near Bothwell which drains South Lake; it shifts east or west each year depending on the winter’s storms and tides, and has consistently been moving east for the past hundred years or so.  The Greenwich dunes "Commons", as they appeared in 1935. Note the proximity of farmer's fields to the sand. Courtesy Government of Prince Edward Island. The Greenwich dunes "Commons", as they appeared in 1935. Note the proximity of farmer's fields to the sand. Courtesy Government of Prince Edward Island. And so it is these shifting sands which leads to our story. As the tale goes, Mr. Lambert VanOmme (originally from Holland), and his friend Herman, were walking across the sand dunes in the Commons, when, entirely unexpectedly, they came across the remnants of an old tree rising out of the sand, above their heads. Neither men, in all of their time living there, had ever seen this tree before. And to make things even stranger, resting beside the tree was an ancient looking axe, one of the old fashioned two-bitted blades. This was a cause for concern for these two men, as there were no footprints leading from the tree into the sand, leaving no evidence of how the mysterious tree or axe could have appeared (1). Amazed by the discovery, Mr. Lambert took the axe with him, and back on the farm he showed it to his neighbour, Mr. Cyril Sanderson. Cyril listened to Mr. Lambert’s story, and he couldn’t believe his eyes when he saw the axe which Mr. Lambert held. Cyril recognized the blade immediately. “That’s Leith’s Sanderson’s axe,” he told Mr. Lambert with incredulity. Cyril explained that he and Leith had been walking through the Commons, decades ago, when some early winter weather set in. The two were in a hurry to get home, and Leith had leaned the axe against the tree, intending to return for it the next day. However the sand moved in upon it and buried it along with the tree, as fast as that. And just as quickly as it had been buried, it was unearthed, entirely unmoved in the place it had last been set. As Cyril added, “the wind can carry the sand faster than any backhoe can take it.” (1)  Meacham's 1880 Atlast possibly illustrates a portion of the Curing Spring. Meacham's 1880 Atlast possibly illustrates a portion of the Curing Spring. The Curing Springs Kings County is known for its abundance of springs, filled with clear, cool water that flows year-round, and it is perhaps even better known for some of the miraculous properties behind these springs. St. Charles has its famous Roaring Springs, Naufrage has its Spring Pool waterfall (complete with stories of fairy sightings), Cobbler’s Spring flows near Basin Head, and the Glen is home to Fountain Head. But of all the springs in the area, there is no story more enthralling than that of the Curing Springs, near Selkirk. Hidden away from the wandering eye, deep in the woods along the Curtis Road, is a small spring which has been known as the Curing Spring for over two hundred years. It is said to cure sickness and illness, either by drinking the water, or by applying it to the body (1). And while this alone would be a sensational claim, the story of its origin makes it all the more intriguing. As the story goes, well over two hundred years ago, there was once a missionary who was travelling in the area who became desperately thirsty. At that time there were few roads and the holy man had no reassurance of when he would next come across a home that could offer him a quenching glass of water. And so he paused, deep in prayer, and pleaded with Providence to provide him the water which he sought. The immediate effects of this prayer remain unknown, but when the missionary later returned to the site of his prayer, he found that, to his amazement, a small spring had emerged out of the ground and was now flowing from that very spot (1). The missionary took it be an indication of divine intervention. The Curing Spring, as it came to be known, was highly regarded by the people of the area, and Hughie Joseph MacDonald remembered seeing a cross erected there, complete with prayer beads and other religious artifacts (1). He also said that anyone who had ever consumed an alcoholic drink would be unable to find the place (1). Whether this remains true, is hard to tell, but the Curing Spring continues to flow to this very day (1).  The famous Nellie J. Banks, under the direction of Captain Dicks, was the leading figure in rum-running off of the north side of Eastern Prince Edward Island. The famous Nellie J. Banks, under the direction of Captain Dicks, was the leading figure in rum-running off of the north side of Eastern Prince Edward Island. Northside Rum Running There are few alive today who fully remember the impact that rum-running had on the Island, but it is still well known that the North shore of King’s County, with the help of ships like the Nellie J. Banks, was one the focal points of the whole ordeal. Prince Edward Island had enacted prohibition early on, ratifying the Scott Act in 1901. This alone was reason enough for Islanders to seek out other means of procuring and imbibing the dangerous drink, but they soon set their sights on a bigger target. In 1920, when the United States enacted prohibition, rum-runners found themselves poised to reap a fortune by supplying smuggled rum to the parched hordes of Americans who now found themselves dry. Fate, it seemed, had dealt island smugglers a perfect hand. The little-known island of St. Pierre and Miquelon, which belongs to France, was one of the only jurisdictions in North America which was not subject to prohibition. And as luck would have it for Island rum-runners, ships departing from St. Pierre and Miquelon were within close proximity to Prince Edward Island’s waters. Once this connection was made, the stage was set, and Islander’s began smuggling rum at an unprecedented rate. The set-up was clever in its simplicity; a twelve-mile limit had been established by the provincial government, and anyone found to be in possession of alcohol within this limit was under the jurisdiction of Prince Edward Island. The waters outside of twelve miles though were anyone’s game. Ships from St. Pierre and Miquelon would be scheduled to arrive at a certain time and place, just outside the limit and always under the cover of night. Local men, typically on fishing boats, would then sail out to meet the ships, buy the rum, and head back to shore. Great care had to be paid though, lest they be apprehended by the authorities, and in response to this ever present threat all manners of cunning schemes were devised to evade authorities. One such scheme was to arrange to meet the French ships based upon the cycles of the tide, so that when the rum was loaded onto the Islander’s boats they would reach the shore at low tide. Then, instead of moving the rum as the police may have expected, it would be buried in the exposed sand bar and hidden away, safe from accidental discovery or interference. That way officers found only empty vehicles at their checkpoints. Several nights later, when there was no tip-off of any rum arrivals, the rum-runners would return to the beach and unearth their buried treasure.  The Glen, located northeast of Souris, provided another convenient hiding place for stashed rum, and offered a hidden transport route from north to south. The Glen, located northeast of Souris, provided another convenient hiding place for stashed rum, and offered a hidden transport route from north to south. But the most clever method of all was one recalled by an old timer who was only a young boy at the time, who was out on one of his first runs when they were intercepted by a police boat. All of the bottles of rum had been hidden in burlap sacks of sugar, but the boy was convinced that the police would still find them. Panicked, he threw all the sacks overboard, where they sunk to the bottom. This ensured that the police found no trace of rum, but the rum-runner was so angry that he threatened to throw the boy overboard. He was spared only by a disturbance which the Captain noticed upon the water. The boy looked, and to his disbelief he saw that the sacks which had sunk to the bottom were now floating alongside the boat. All of the sugar had slowly dissolved, and the rum and floated back to the top. The boy had saved the day, and a new method had been discovered to evade the watchful eyes of the police, something which continued to the very end of prohibition on Prince Edward Island in 1948.  MacKinnon's Mill Stones, as they appear in the Archives of Prince Edward Island. George Leard photo. MacKinnon's Mill Stones, as they appear in the Archives of Prince Edward Island. George Leard photo. MacKinnon’s Mill Stones Sometimes in history it is some of the most seemingly insignificant objects that tell the greatest story. This is certainly the case in the story of MacKinnon’s Mill Stones, which demonstrates the sheer dedication and willpower that our early Island ancestors displayed in carving out a living from what was, at the time, an often inhospitable place. The story began with an Acadian mill that once stood near present day Big Pond. Little is known of this mill, save for the fact that those who once owned it were most likely driven out during the Acadian expulsion. It wasn’t until Archie MacPhee, when he leased this property from landowner John Stewart, began his farm on the Big Pond property that he discovered two large and well crafted mill stones which the Acadians had left behind. One stone weighed in at around 60 pounds, while the other, larger stone was 75 pounds. More crucially, they were engraved with the year 1741, which offered MacPhee a clue as to their origin (2). Simply finding these old stones was story enough, but what makes them remarkable is the story of their journey from Big Pond, on the north side of the Island, to Red Point, on the south side. Archie MacPhee had no use for the stones, and he put them aside as he went about life on his farm. But memory of them remained, and in the 1820s, John MacKinnon, who was newly arrived at Red Point, heard about the Acadian stones (2). He was desperate to establish a mill, and needed stones. There were no other stones available at the time, nor would he have had the money to buy new ones. And so, without any other option, John MacKinnon set out for Big Pond. This trek in itself is noteworthy, for unlike today there was no simple road from Red Point to Big Pond. We know only that he followed “the old French trail” which wound its way through the woods (a trail which could possibly have been a precursor to the present day Baltic Road). Once in Big Pond he negotiated the purchase of the mill stones from Archie MacPhee, but MacKinnon was still faced with the colossal task of getting them home, a distance of some 15 kilometres. Undaunted, MacKinnon rose to the challenge. As Deacon Scott recounted the story in the 1890s, MacKinnon padded the shoulders of his shirt with sod, and then by passing a spike through the center of the mill stone he gripped it and lifted it onto his back (2). Then the tedious work began; step by step MacKinnon made his way south with the burdensome load, until he had progressed the distance of a mile. There he stopped, set down the weight, and returned to MacPhee’s farm for the second stone. This he carried a mile before stopping to rest beside its brother. After a time he resumed his labour, carrying the stone another mile. This he repeated, walking each mile thrice, with two of the three under the burden of a stone, until he had reached his home at Red Point (2). This Herculean feat proved to be John MacKinnon’s greatest doing, as the story was told for years to come. The stones were employed near Little Harbour, at what is today known as MacKinnon’s Point, named after the very man who brought them there. The stones themselves received great recognition as well; they once ground the meal to serve Bishop MacEachern when he visited, and today they reside in the Prince Edward Island Archives (2).  A late 1800s trade card depicting the apparition of a forerunner. A late 1800s trade card depicting the apparition of a forerunner. Bear River's Forerunner Certainly anyone familiar with Island lore has heard tell of the forerunner: a ghostly spectre whose appearance is said to foretell impending disaster or loss. Forerunners often appear as a visual premonition of sorts, an impossible visit or conversation with an ailing loved one, or the sighting of something that couldn’t possibly be, only to find out that it was a vision of what was to come. Tales of forerunners stretch from St. Peter’s, up the north side through Monticello, all the way to East Point. One story of an encounter with a forerunner which is particularly memorable is that of Denny Costello (3). Denny was an avid fisherman, and one night, after a long day fishing at Naufrage, he was walking home alone down the Bear River road. Night had fallen, and as the human mind is wont to do, Denny began to imagine that he was seeing things that were not there. He did his best to dispel the notion, but he could not shake the feeling that he was not entirely alone. This sense of presence continued as he walked down the dark, lonely road, until at last he spotted the cause of his vexation. There, ahead of him on the road, was a dark figure. Denny stopped suddenly in his tracks, eyes locked on the apparition before him, and the creature stopped too. Eyes trained on this menace, Denny took a few steps forward, but the figure retreated, as if to evade him. He slowed to a crawl, taking cautious steps onward, but so too did the creature. Terrified, Denny removed his cap, said a prayer, and blessed himself. When he donned the cap once more and looked ahead of him on the road, the creature had disappeared entirely, as if it had never been there. Relieved, Denny hurried home, thanking the Lord for His intervention and not wishing to test his faith any further. All the way home Denny’s mind replayed the scenario in his head, and he could make no sense of it. It wasn’t until he was in his porch, by the lamplight, that he removed his cap and found that a long thread had been torn loose by a snag when he had been fishing. This thread, he discovered, was just long enough to dangle in front of his vision as he had walked down the road, a fitting explanation for his otherworldly vision. As Kay MacIsaac tells, this became a popular topic of torment for poor Denny. From then on, when someone met him on the road, the greeting was always “Hey Denny, did you see any forerunners this evening?” (3) If you enjoyed this article, be sure to like us on Facebook, share it with your friends, and leave a comment below. We happily receive memories, photos, and stories as inspiration for our next article. References:

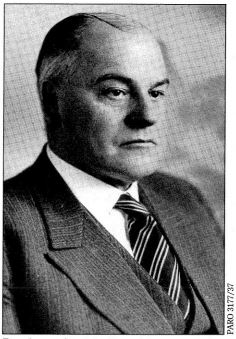

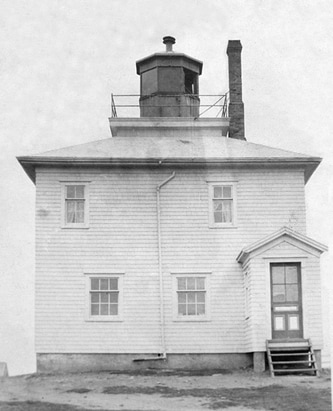

1. Rossiter, Juanita. Gone to the Bay. 2000. Accessed via UPEI. 8 March 2017. Print. 2.Townshend, Adele. Ten Farms Become a Town. 1986. Print. 3. MacIsaac, Kay. Fun, Frolic, and Forerunners. 1998. Print. 4. Historical Sketch of Eastern Kings. 1973. Print. 5. MacDonald, Roddie J. History of St. Margaret’s Parish – Bear River – P. E. Island. Accessed via The Island Register. 1982. Web. 9 March 2017. 6. Hornby, Jim. "Bear Facts: History and Folklore of Island Bears, Part Two" The Island Magazine, 1987, vol 22. 9 March 2017. Web. Eastern Prince Edward Island has a diverse and fascinating history, filled with stories that have been handed down from one generation to another. The Red Rock Adventure Company is proud to share and preserve these tales, and some of the most memorable ones have been related below. If you like our work, please be certain to like us on Facebook, and to share these articles with your friends. Don't hesitate to contact us with corrections, photos, or suggestions for our next article.  MacMillan's house would not have been much different than the building pictured in the background here. MacMillan's house would not have been much different than the building pictured in the background here. North Lake’s Floating House (1923) Homes weren’t always as sturdy as they are today, and many people lived as best as they could afford. This sometimes led to people building their home in less than ideal places, such as too near the shore, or even on the sand. Such was the case with Joseph MacMillan and his family at North Lake. They were living very near to the shore in a building at North Lake which had been owned by Matthew & MacLean (1). One night there was a powerful storm surge, and owing to the lack of sand dunes at North Lake at the time, the little house and all of its occupants were washed straight across North Lake, landing in Kenneth Fraser’s field. The house remained completely intact in the move (1). The family was jarred awake by this sudden disruption, and all were forced to scramble upstairs as the surging waters worked its way into the house. A plank was extended from the upstairs window, and the entire family slid down the plank to make a safe escape (1). The house was later found to be beyond repair. Axe Handle Night: Souris’ Worst Riot (12 October 1888) The 1880s was a fighting period among the youth of the Souris area, as it was in many other parts of the Island, and the availability of cheap and accessible liquor did little to improve matters (2). Souris at the time was also home to numerous hotels which welcomed unknown visitors to the area year round, and its harbour was always filled with boisterous seamen who bunked on their own ships. As such, it was a perfect storm for those looking to start trouble (2). And while there had been clashes before, there is nothing yet that rivals Axe Handle Night. The incident began near the old Carleton store around 8 o’clock in the evening (2). Joseph Doyle, a Souris merchant and banker, was spotted being attacked by drunken sailors. James Dunphy, a Souris saddler, ran to his rescue, and soon they were both badly injured. The alarm was raised, and a throng of locals took to the streets against these rioting fishers. Both sides armed themselves with sticks and axe handles (2). Further clashes ensued, but the Souris locals were successful in driving these unruly men back towards the wharf. Several rioters were captured and locked up for the night (2). Things did not end so well for everyone, however. One sailor, a Joseph Strople, was fleeing from those Souris men, and in his drunkenness did not make the turn onto Breakwater Street. Instead he careened over the bank, near the present day Sailor’s Memorial, and tumbled to his death upon the rocks (2). The rioters who were arrested that night were each fined $50, which was considered to be a large and excessive fine at that time. Other charges included “fighting on the shore on the Sabbath”, for which those found guilty were charged $2, and being “drunk and disorderly”.  Before the harbour was opened, fishermen were forced to set sail from shore. Before the harbour was opened, fishermen were forced to set sail from shore. North Lake Harbour Opens (7 December 1917) To view North Lake one hundred years ago would be to view a very different sight. At that time North Lake was very much a freshwater lake. Fed then, as it is today, by water from Fountain Head, there were only a few small streams permitting overflow to escape to into the Gulf of St. Lawrence, and there was no harbour for fishing whatsoever (1). Efforts were made to cut a channel from the lake to the present day opening of the harbour, as it was deemed to be the ideal location, but the hand tools available to the workers at that time made the job an impossibility. Consider the amazement then, on the stormy morning of December 7 1917, when word spread around that a storm surge had broken open the sand around the lake and had joined it to the ocean (1). In 1922 the first bridge was built, and North Lake has boomed as a fishing harbour ever since.  Ice foes, similar to these in Georgetown, brought countless seals to the men in Red Point. Ice foes, similar to these in Georgetown, brought countless seals to the men in Red Point. The Red Point Seal Hunt (April 1846) Funds and supplies had grown low after a long winter in Red Point, and residents of the area were longing for the warmth of spring. But instead of spring winds, April brought forth a terrible easterly gale which was sufficient to send a massive sheet of ice onto Red Point beach (1). Some men went down to investigate this April ice, and to their surprise they found that it was populated by countless seals. These seals, which would normally bear their pups far out at sea, had been carried by the wind to Red Point, and the local men headed quickly for the ice field to hunt them (1). The work was highly profitable, given the vast number of seals, but the men became so engrossed in the task that they failed to notice that the wind had shifted, and just as it had carried the seals inland, it had now washed these men out to sea. Things looked dire indeed: they had no provisions, night was falling, and all of their own fishing boats had been hauled up onto shore for the winter. Luckily, those who remained onshore noted the growing absence of the men, and had wits enough about them to launch the boats and embark upon a rescue mission. Such quick action proved to be the saving grace of the seal hunters, who otherwise would have perished at sea. No lives were lost as all the men piled into the small rescue boats, but no space remained for the dozens of seal pelts which the men had worked so hard far. These were abandoned, and the next morning a Dutch sealing schooner could be seen taking on board those pelts which the Red Point crew had worked so hard for (1). The First Car In Souris (~1915) The development of roadways in the Souris area was a process which took place over the past 200 years, and one that is arguably still taking place to this day. Roads in the town of Souris proper are speculated to have originally been cow paths (2), and even what is present day Route 2 began merely as a series of interconnected trails leading from one farm to another. It wasn’t until 1820 that an official road was established connecting the Fortune area to what would become the Town of Souris. Even as the 20th century dawned and rumors of the automobile began to make their way towards Eastern PEI, the roadway remained less than desirable. Individual land owners still retained rights to the property which the road was on, and as such the road was impeded by countless fences, posts, and gates which were intended to keep their livestock on their own property. A rider or motorist would be forced, at every property, to dismount and open the gate, drive through, and then latch the gate behind him. This proved to be problematic, and Charles Wright, Overseer of Roads, ordered the removal of “all fences, swinging gates, bars or other obstructions placed in the road at the expense of the offending party”, or else they would face a fine (2). It should also be noted that this decree forbid road construction workers from “illegally stopping travellers to obtain rum.” As for the first car in Souris, the claim is a much disputed one. Doc Smallwood owned an early 490 Chevrolet (likely a 1915), while Erskine P. Stavert, the bank manager, is remembered to have competed in an impromptu race with a horse in the early days of motoring. Most memorable though was the arrival of Arthur McQuaid’s Briscoe car. Finlay McLeod drove it home from Charlottetown for him on a rainy day; it was a road closed day but he had a special permit. A local blacksmith in the Marshfield area, existentially threatened by cars and their new way of life, threatened to assail McLeod with a heavy hammer as he crossed through his property, and it took much convincing for him (and the car) to escape unscathed.  Dr. Augustine MacDonald Dr. Augustine MacDonald The Miracle Operation (1908) To this day Dr. Gus is remembered almost as folk hero in the Souris area, and perhaps rightly so. His caring, commitment, and dedication to the people of this area was unwavering and unparalleled, and had it not been for him, tragedy would have struck the area more times than one would like to imagine. While Dr. Gus is much remembered for delivering babies and healing the sick (not to mention his death-bed request to mark every bill owing in his ledger as “paid”), but he is surely most remembered for the miracle operation he performed upon the young A.J. MacCormack in 1908 (3). Poor A.J., who was only four years old at the time, was run over by a mower while he was in the grain field near his home in St. Margarets, severing his feet from his legs (3). By the time Dr. Gus arrived, several hours later, it was thought that the legs and feet would need to be amputated entirely to avoid the risk of a fatal infection (3). A.J.’s mother would not accept this fate for her son, and she refused to let the doctor leave until he agreed to try to save the feet (3). Dr. Gus placed the unconscious boy on the kitchen table, washed his feet in a solution of water and bichloride mercury, and operated for several hours. As Dr. Gus would later remark, only a few tendons and blood vessels remained (3). To the amazement of all, surely even the doctor, the operation was a success, and A.J. learned to walk again, albeit with a limp. The story was published on the front page of The Guardian, and is still told in local folklore today (3).  Naufrage Lighthouse as it appeared in 1917. Image provided via Lighthouse Friends, courtesy of the Canadian Coast Guard. Naufrage Lighthouse as it appeared in 1917. Image provided via Lighthouse Friends, courtesy of the Canadian Coast Guard. Naufrage Lighthouse Keeper (1917) Naufrage, the French word for shipwreck, is an aptly named place, as it has a past littered with wreckage and tragedy against the merciless sea. In fact, the first settlers to area were survivors of a shipwreck, and this tendency for wrecks against the unyielding rocks of the Naufrage coast has continued for centuries to come. Given this, there was a strong desire to erect a lighthouse at Naufrage, in hopes of saving innocent lives at sea. And so, in 1913, a lighthouse was built on the western side of the present day Naufrage bridge (4). Frank MacKinnon served as the first lighthouse keeper until 1917, when he tragically drowned on setting day while working on the water (4). Even with Frank’s death it was essential that the lighthouse remain operational, especially with so many lobster fishermen out on the water, and Frank’s son Neil, who was only 8 years old at the time, was the only one who knew how to operate it. Despite the loss of his father, Neil rose to the occasion and instructed the men of the community on the operation of the light, and thanks to his fortitude no other lives were lost that terrible night (4). This still left Naufrage without a lighthouse keeper, and so Frank’s wife Sarah stepped into the role. It was quite unusual to have a woman as a lighthouse keeper, but Sarah rose to the occasion. When one night the mechanism that rotated the light broke down, Sarah spent the entire night revolving the lens by hand. She later received a letter of commendation from a passing captain at having held her post so diligently. Sarah MacKinnon certainly proved her mettle, and she held the job as lighthouse keeper until 1922. The Red Rock Adventure Company is the Island's number one destination for guided bicycle tours. If you liked this article, please like us on Facebook and share with your friends. References:

1. Historical Sketch of Eastern Kings. 1973. Print. 2. Townshend, Adele. Ten Farms Become a Town. 1986. Print. 3. Mullally, Sasha. Dr. Roddie and Dr. Gus: The Golden Age of Medicine. The Island Magazine. 1997. Print. 4. Shipwreck Point Lighthouse. Lighthouse Friends Online. 5 March 2017. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed