|

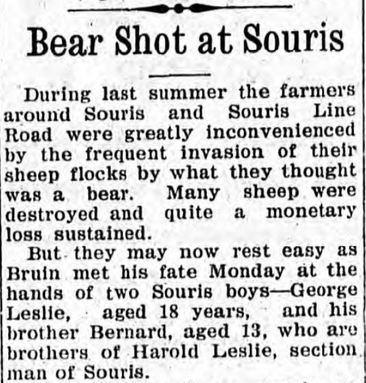

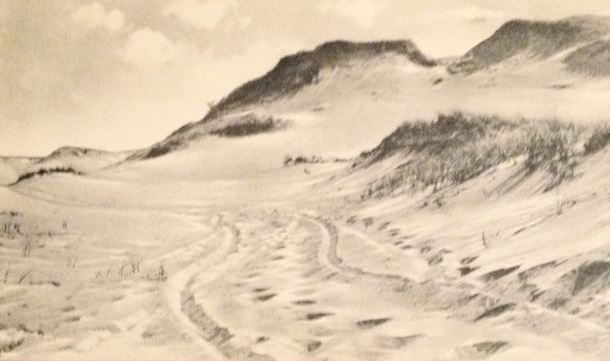

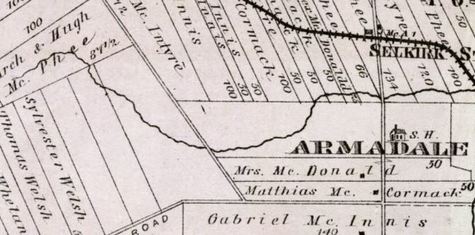

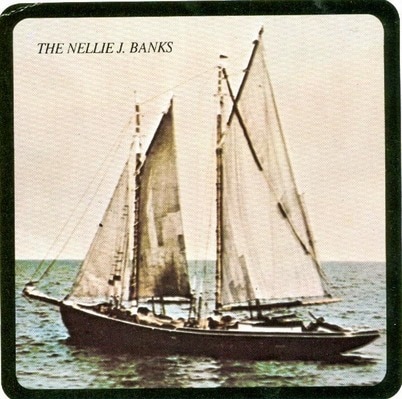

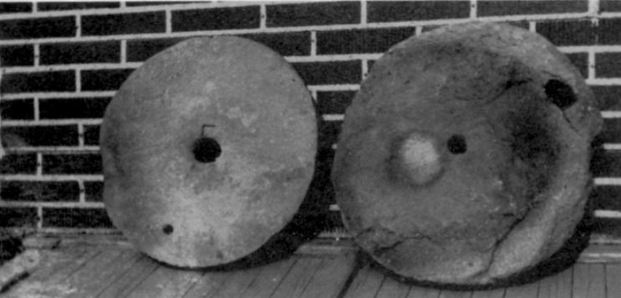

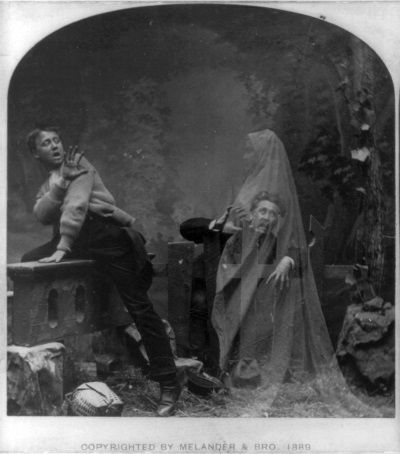

This article is the second in a series which continues to explore the rich history and heritage of Eastern Prince Edward Island. It is our hope that these stories provide you with a taste of what our cultural tours have to offer. To read an earlier installment of stories, click here.  To spot a bear in the woods was a fearsome sight indeed. 1930s post card. To spot a bear in the woods was a fearsome sight indeed. 1930s post card. The Last Great Bear Island history is rife with stories of bears, such that they almost border on legend. An ever present danger in the lives of early Island settlers, stories and fears of bears permeated the minds of these people, and even the sighting of a bear was enough to set the hearts and minds of Islanders on edge. At Norris Pond, near Souris, it is remembered that a bear once attacked a man walking home from the pond. The bear pounced upon the man, who was taken by surprise and caught completely off guard. He had no weapon with which to defend himself, and so in desperation he drove his arm down the bear’s throat and pulled out his organs, thus killing him. Another story from Red Point relates the untimely death of a bull at the hands of a bear. The bear, seeing the bull alone in the field, attacked it in a rage, climbing upon the poor creature. The bull though was not to go down without a fight. It carried the bear upon its back as it ran wildly towards the farmyard, and it was later, after the bear had proven victorious, that the farmer could see the desperate claw marks of the bear against the trees as it struggled to keep hold of the raging bull (4). And while the entire Island encountered their fair share of bears over the years, one would not be amiss to suggest that Eastern Prince Edward Island shared a particular connection to the bruin lot. In fact, it had been reported in The Guardian, as early as 1862, that "bears are becoming very numerous and exceedingly troublesome east of Souris.”  Islanders have long been intrigued by power and majesty of the bear. This "dancing bear", chained to its owners, appeared in Charlottetown in 1890s. PARO PEI Photo. Islanders have long been intrigued by power and majesty of the bear. This "dancing bear", chained to its owners, appeared in Charlottetown in 1890s. PARO PEI Photo. One need only look at the places which “bear” the name of the fearsome creature to understand what role they played in the pioneer psyche. Basin Head was once named Bear Harbour (4), as was Black Pond (Loch Dhu), while today’s Little Harbour beach had a unique stoney outcropping called Bear Rock. These names have largely disappeared, save for Bear River, which retains its reference to its grizzly past. The place boasts a dual claim to the animal; both from a time when it was known to foster many bears along the river, and more memorably, when one of the early settlers, Roderick MacDonald, fought and killed a large bear with his bare hands. (5) But most notorious of all in the Souris area is the story of the last great bear, a story which is known across the Island. According to Hornby, the last bear to have been killed on Prince Edward Island was killed on 7 February 1927. It was shot on the Souris Line Road by George and Bernard Leslie, who were 16 and 18 at the time, respectively. The event was reported on as the headline for the Evening Patriot on 8 February 1927 (6), and in The Guardian the next morning. It all began when the boys noticed the tracks of a bear crossing the north end of Souris Line Road, heading east. There had a been a spring thaw, and the boys knew that a bear would be active in that sort of weather. They didn’t tell their father about the sighting, saying that “he’d ruin the whole thing on us; he’d have to come”(6). Instead, they waited until the next day, until their father had left for Souris. With him gone, the hunt was on.  Taken from The Guardian. 9 February 1927. Taken from The Guardian. 9 February 1927. They tracked the bear all through morning, and it wasn’t until about one o’clock in the afternoon that they found it. It was risky work, following the trail of a wild bear, as it could have appeared from the thickets at any time. Doggedly the boys pursued their target, until at last, through the undergrowth, they spotted the animal. To their surprise, it was asleep. The boys held the perfect vantage point from the thickets, and George made the first move. He fired his shotgun from a distance of about 15 feet, striking the bear in the hip. The next shot caught it in the side of the neck. The bear sprang onto its hind legs, bellowing in a rage, but the boys didn’t retreat. The bear was clearly injured, and it soon fell to the ground in weakness. George stepped closer to his prize and took one more shot at it. Gunfire rang out, the clearing fell silent, and the Island's last great bear was dead. The carcass weighed over 400 pounds, and was skinned on the spot by the two boys. It was later boiled for its grease, and the grease was sent to England. For the grease they received $14, a considerable sum for two young boys at the time.  Greenwich was once a prominent farming locale. Greenwich was once a prominent farming locale. The Shifting Sands It seems fitting to include an entry about Greenwich National Park, as for the 2017 season all National Parks are open free to the public to celebrate Canada’s 150th birthday. Greenwich has a long and colorful history, dating all the way back to the Mi’Kmaq who fished off of its shores, and was a home to the earliest French settlers who migrated there from their shipwreck at Naufrage. For many years, before it was designated a National Park, the land around Greenwich was even farmed by locals in the area. Many changes have taken place at Greenwich throughout this time, but one thing that has always remained constant is the shifting sand dunes which dominate the area. In the years surrounding the turn of the twentieth century, the Greenwich sand dunes were as imposing as ever. In those days they were known as “the Commons”, and were fenced in entirely (1). Within the Commons all of the local farmers’ animals were set to pasture, and they would not need to be collected until the fall when the cool weather set it. Each animal was marked with the farmer’s specific brand, so that the animal could be distinguished (1). The Commons, it seems, was little good for much else, as any Islander who has lived near the shore can tell you. The sand is just too unpredictable. Take for example the flow of Cow River, which can, on the nightly, reset its course across the sands and in the morning appear as a new river entirely. Or, consider the open run near Bothwell which drains South Lake; it shifts east or west each year depending on the winter’s storms and tides, and has consistently been moving east for the past hundred years or so.  The Greenwich dunes "Commons", as they appeared in 1935. Note the proximity of farmer's fields to the sand. Courtesy Government of Prince Edward Island. The Greenwich dunes "Commons", as they appeared in 1935. Note the proximity of farmer's fields to the sand. Courtesy Government of Prince Edward Island. And so it is these shifting sands which leads to our story. As the tale goes, Mr. Lambert VanOmme (originally from Holland), and his friend Herman, were walking across the sand dunes in the Commons, when, entirely unexpectedly, they came across the remnants of an old tree rising out of the sand, above their heads. Neither men, in all of their time living there, had ever seen this tree before. And to make things even stranger, resting beside the tree was an ancient looking axe, one of the old fashioned two-bitted blades. This was a cause for concern for these two men, as there were no footprints leading from the tree into the sand, leaving no evidence of how the mysterious tree or axe could have appeared (1). Amazed by the discovery, Mr. Lambert took the axe with him, and back on the farm he showed it to his neighbour, Mr. Cyril Sanderson. Cyril listened to Mr. Lambert’s story, and he couldn’t believe his eyes when he saw the axe which Mr. Lambert held. Cyril recognized the blade immediately. “That’s Leith’s Sanderson’s axe,” he told Mr. Lambert with incredulity. Cyril explained that he and Leith had been walking through the Commons, decades ago, when some early winter weather set in. The two were in a hurry to get home, and Leith had leaned the axe against the tree, intending to return for it the next day. However the sand moved in upon it and buried it along with the tree, as fast as that. And just as quickly as it had been buried, it was unearthed, entirely unmoved in the place it had last been set. As Cyril added, “the wind can carry the sand faster than any backhoe can take it.” (1)  Meacham's 1880 Atlast possibly illustrates a portion of the Curing Spring. Meacham's 1880 Atlast possibly illustrates a portion of the Curing Spring. The Curing Springs Kings County is known for its abundance of springs, filled with clear, cool water that flows year-round, and it is perhaps even better known for some of the miraculous properties behind these springs. St. Charles has its famous Roaring Springs, Naufrage has its Spring Pool waterfall (complete with stories of fairy sightings), Cobbler’s Spring flows near Basin Head, and the Glen is home to Fountain Head. But of all the springs in the area, there is no story more enthralling than that of the Curing Springs, near Selkirk. Hidden away from the wandering eye, deep in the woods along the Curtis Road, is a small spring which has been known as the Curing Spring for over two hundred years. It is said to cure sickness and illness, either by drinking the water, or by applying it to the body (1). And while this alone would be a sensational claim, the story of its origin makes it all the more intriguing. As the story goes, well over two hundred years ago, there was once a missionary who was travelling in the area who became desperately thirsty. At that time there were few roads and the holy man had no reassurance of when he would next come across a home that could offer him a quenching glass of water. And so he paused, deep in prayer, and pleaded with Providence to provide him the water which he sought. The immediate effects of this prayer remain unknown, but when the missionary later returned to the site of his prayer, he found that, to his amazement, a small spring had emerged out of the ground and was now flowing from that very spot (1). The missionary took it be an indication of divine intervention. The Curing Spring, as it came to be known, was highly regarded by the people of the area, and Hughie Joseph MacDonald remembered seeing a cross erected there, complete with prayer beads and other religious artifacts (1). He also said that anyone who had ever consumed an alcoholic drink would be unable to find the place (1). Whether this remains true, is hard to tell, but the Curing Spring continues to flow to this very day (1).  The famous Nellie J. Banks, under the direction of Captain Dicks, was the leading figure in rum-running off of the north side of Eastern Prince Edward Island. The famous Nellie J. Banks, under the direction of Captain Dicks, was the leading figure in rum-running off of the north side of Eastern Prince Edward Island. Northside Rum Running There are few alive today who fully remember the impact that rum-running had on the Island, but it is still well known that the North shore of King’s County, with the help of ships like the Nellie J. Banks, was one the focal points of the whole ordeal. Prince Edward Island had enacted prohibition early on, ratifying the Scott Act in 1901. This alone was reason enough for Islanders to seek out other means of procuring and imbibing the dangerous drink, but they soon set their sights on a bigger target. In 1920, when the United States enacted prohibition, rum-runners found themselves poised to reap a fortune by supplying smuggled rum to the parched hordes of Americans who now found themselves dry. Fate, it seemed, had dealt island smugglers a perfect hand. The little-known island of St. Pierre and Miquelon, which belongs to France, was one of the only jurisdictions in North America which was not subject to prohibition. And as luck would have it for Island rum-runners, ships departing from St. Pierre and Miquelon were within close proximity to Prince Edward Island’s waters. Once this connection was made, the stage was set, and Islander’s began smuggling rum at an unprecedented rate. The set-up was clever in its simplicity; a twelve-mile limit had been established by the provincial government, and anyone found to be in possession of alcohol within this limit was under the jurisdiction of Prince Edward Island. The waters outside of twelve miles though were anyone’s game. Ships from St. Pierre and Miquelon would be scheduled to arrive at a certain time and place, just outside the limit and always under the cover of night. Local men, typically on fishing boats, would then sail out to meet the ships, buy the rum, and head back to shore. Great care had to be paid though, lest they be apprehended by the authorities, and in response to this ever present threat all manners of cunning schemes were devised to evade authorities. One such scheme was to arrange to meet the French ships based upon the cycles of the tide, so that when the rum was loaded onto the Islander’s boats they would reach the shore at low tide. Then, instead of moving the rum as the police may have expected, it would be buried in the exposed sand bar and hidden away, safe from accidental discovery or interference. That way officers found only empty vehicles at their checkpoints. Several nights later, when there was no tip-off of any rum arrivals, the rum-runners would return to the beach and unearth their buried treasure.  The Glen, located northeast of Souris, provided another convenient hiding place for stashed rum, and offered a hidden transport route from north to south. The Glen, located northeast of Souris, provided another convenient hiding place for stashed rum, and offered a hidden transport route from north to south. But the most clever method of all was one recalled by an old timer who was only a young boy at the time, who was out on one of his first runs when they were intercepted by a police boat. All of the bottles of rum had been hidden in burlap sacks of sugar, but the boy was convinced that the police would still find them. Panicked, he threw all the sacks overboard, where they sunk to the bottom. This ensured that the police found no trace of rum, but the rum-runner was so angry that he threatened to throw the boy overboard. He was spared only by a disturbance which the Captain noticed upon the water. The boy looked, and to his disbelief he saw that the sacks which had sunk to the bottom were now floating alongside the boat. All of the sugar had slowly dissolved, and the rum and floated back to the top. The boy had saved the day, and a new method had been discovered to evade the watchful eyes of the police, something which continued to the very end of prohibition on Prince Edward Island in 1948.  MacKinnon's Mill Stones, as they appear in the Archives of Prince Edward Island. George Leard photo. MacKinnon's Mill Stones, as they appear in the Archives of Prince Edward Island. George Leard photo. MacKinnon’s Mill Stones Sometimes in history it is some of the most seemingly insignificant objects that tell the greatest story. This is certainly the case in the story of MacKinnon’s Mill Stones, which demonstrates the sheer dedication and willpower that our early Island ancestors displayed in carving out a living from what was, at the time, an often inhospitable place. The story began with an Acadian mill that once stood near present day Big Pond. Little is known of this mill, save for the fact that those who once owned it were most likely driven out during the Acadian expulsion. It wasn’t until Archie MacPhee, when he leased this property from landowner John Stewart, began his farm on the Big Pond property that he discovered two large and well crafted mill stones which the Acadians had left behind. One stone weighed in at around 60 pounds, while the other, larger stone was 75 pounds. More crucially, they were engraved with the year 1741, which offered MacPhee a clue as to their origin (2). Simply finding these old stones was story enough, but what makes them remarkable is the story of their journey from Big Pond, on the north side of the Island, to Red Point, on the south side. Archie MacPhee had no use for the stones, and he put them aside as he went about life on his farm. But memory of them remained, and in the 1820s, John MacKinnon, who was newly arrived at Red Point, heard about the Acadian stones (2). He was desperate to establish a mill, and needed stones. There were no other stones available at the time, nor would he have had the money to buy new ones. And so, without any other option, John MacKinnon set out for Big Pond. This trek in itself is noteworthy, for unlike today there was no simple road from Red Point to Big Pond. We know only that he followed “the old French trail” which wound its way through the woods (a trail which could possibly have been a precursor to the present day Baltic Road). Once in Big Pond he negotiated the purchase of the mill stones from Archie MacPhee, but MacKinnon was still faced with the colossal task of getting them home, a distance of some 15 kilometres. Undaunted, MacKinnon rose to the challenge. As Deacon Scott recounted the story in the 1890s, MacKinnon padded the shoulders of his shirt with sod, and then by passing a spike through the center of the mill stone he gripped it and lifted it onto his back (2). Then the tedious work began; step by step MacKinnon made his way south with the burdensome load, until he had progressed the distance of a mile. There he stopped, set down the weight, and returned to MacPhee’s farm for the second stone. This he carried a mile before stopping to rest beside its brother. After a time he resumed his labour, carrying the stone another mile. This he repeated, walking each mile thrice, with two of the three under the burden of a stone, until he had reached his home at Red Point (2). This Herculean feat proved to be John MacKinnon’s greatest doing, as the story was told for years to come. The stones were employed near Little Harbour, at what is today known as MacKinnon’s Point, named after the very man who brought them there. The stones themselves received great recognition as well; they once ground the meal to serve Bishop MacEachern when he visited, and today they reside in the Prince Edward Island Archives (2).  A late 1800s trade card depicting the apparition of a forerunner. A late 1800s trade card depicting the apparition of a forerunner. Bear River's Forerunner Certainly anyone familiar with Island lore has heard tell of the forerunner: a ghostly spectre whose appearance is said to foretell impending disaster or loss. Forerunners often appear as a visual premonition of sorts, an impossible visit or conversation with an ailing loved one, or the sighting of something that couldn’t possibly be, only to find out that it was a vision of what was to come. Tales of forerunners stretch from St. Peter’s, up the north side through Monticello, all the way to East Point. One story of an encounter with a forerunner which is particularly memorable is that of Denny Costello (3). Denny was an avid fisherman, and one night, after a long day fishing at Naufrage, he was walking home alone down the Bear River road. Night had fallen, and as the human mind is wont to do, Denny began to imagine that he was seeing things that were not there. He did his best to dispel the notion, but he could not shake the feeling that he was not entirely alone. This sense of presence continued as he walked down the dark, lonely road, until at last he spotted the cause of his vexation. There, ahead of him on the road, was a dark figure. Denny stopped suddenly in his tracks, eyes locked on the apparition before him, and the creature stopped too. Eyes trained on this menace, Denny took a few steps forward, but the figure retreated, as if to evade him. He slowed to a crawl, taking cautious steps onward, but so too did the creature. Terrified, Denny removed his cap, said a prayer, and blessed himself. When he donned the cap once more and looked ahead of him on the road, the creature had disappeared entirely, as if it had never been there. Relieved, Denny hurried home, thanking the Lord for His intervention and not wishing to test his faith any further. All the way home Denny’s mind replayed the scenario in his head, and he could make no sense of it. It wasn’t until he was in his porch, by the lamplight, that he removed his cap and found that a long thread had been torn loose by a snag when he had been fishing. This thread, he discovered, was just long enough to dangle in front of his vision as he had walked down the road, a fitting explanation for his otherworldly vision. As Kay MacIsaac tells, this became a popular topic of torment for poor Denny. From then on, when someone met him on the road, the greeting was always “Hey Denny, did you see any forerunners this evening?” (3) If you enjoyed this article, be sure to like us on Facebook, share it with your friends, and leave a comment below. We happily receive memories, photos, and stories as inspiration for our next article. References:

1. Rossiter, Juanita. Gone to the Bay. 2000. Accessed via UPEI. 8 March 2017. Print. 2.Townshend, Adele. Ten Farms Become a Town. 1986. Print. 3. MacIsaac, Kay. Fun, Frolic, and Forerunners. 1998. Print. 4. Historical Sketch of Eastern Kings. 1973. Print. 5. MacDonald, Roddie J. History of St. Margaret’s Parish – Bear River – P. E. Island. Accessed via The Island Register. 1982. Web. 9 March 2017. 6. Hornby, Jim. "Bear Facts: History and Folklore of Island Bears, Part Two" The Island Magazine, 1987, vol 22. 9 March 2017. Web.

11 Comments

Mary Dunford

3/12/2017 10:29:38 am

I'm the daughter of John J Wilford ,Clement ,McDonald . We lived at the end of New Zealand Rd. called clear springs. We moved away I think around 1953 and returned back in 1964. I love to hear any stories from around the East End of the island. My mother came from Bear River she was a Hughes.I moved back to Toronto in 1969. Please keep the stories coming.

Reply

Glen R. Stewart

3/12/2017 01:35:28 pm

Very interesting stories - heard some of them when living at Red Point some 70 years ago....

Reply

Red Rock

3/13/2017 09:40:39 am

Hello Glen, if you have any more stories we would love to hear them. Call us at 902 215 0029, or email us at [email protected]

Reply

Norma Jean (Bennett-MacDonald) Killam

3/12/2017 03:04:28 pm

There were lots of bear stories from the eastern parts of Kings County, ie East Baltic to East Point areas when I was younger

Reply

Red Rock

3/12/2017 06:43:24 pm

That's great information! If you are able to track any stories down, please let us know!

Reply

Sandra McDevitt

3/13/2017 10:29:31 am

My mother told me a forerunner story about my Aunt Viola Cheverie. She and a friend were in a horse and buggy riding down the road when suddenly the horse reared and looking to the side of the road they saw several bodies of men placed in the side of the road beside each other. Not long after there was a shipwreck and the bodies were laid exactly where my aunt saw them. The farm was in Fairfield and it would have been sometime around 1932. Do you know of any shipwrecks in the area at that time. If memory serves me correctly, the men were of some foreign nationality.

Reply

Adele Shea

3/13/2017 01:28:30 pm

I am loving the stories about Souris and surrounding area's. My sister and I have spent many hours in the area over this past few summers. We were looking for our ancestors. Our mother was born in Souris (Farmington) but left when she was around 3 years old so we really didn't have much information. We met a lovely man in 2015 at an auction in Souris and when we got talking to him he was able to give us a lot of information. We have visited him a few times since. A lot of mom's relatives remained in Souris. My great grandfather was Alfred MacDonald married to Elizabeth (Stewart) MacDonald. I heard from a granddaughter of Aide & Viney MacDonald that someone in the family may be doing a family tree. Would love to hear from them.

Reply

Sandra McDevitt

3/14/2017 11:46:27 am

Realizing there are lots of PEI McDonalds I wonder if your family had a Charlie McDonald who drowned in 1938. He was engaged to my Aunt Viola Cheverie.

Reply

Adele Shea

3/14/2017 01:21:09 pm

Thanks for the comment. Not sure if he would have been a relative or not. Have not heard about this very sad story. We have/had a Charlie R. MacDonald son of Joseph A. and Margaret MacDonald. He was a cousin of my grandfather, George MacDonald and Charlie married my grandmother's sister Adele (Cullen) MacDonald. Charlie died in Ch'town 1975 and his wife Adele passed away years later but I do not have the year. It does not appear in her death notice.

Joan mac phee

3/13/2017 10:32:53 pm

Found your site by accident, what great stories you have. I hope I can continue to read more. I was born in Souris, lived in Black Pond. I've lived in Edmonton for over thirty years and love my pei roots and history. Please print more stories thank you for the memories in history.

Reply

1/31/2019 01:19:03 pm

Among the stories that you have cited, I am sure that I haven't read any story that you have featured there. By just having an overview of what these stories are all about, I was able to see that you love things and stories about bears. Well, there might be a deeper reason about this matter, But I really understand why you chose to read stories like that. Bears have always been very interesting because of their behaviors. The fact that you study them makes you cool too!

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed