|

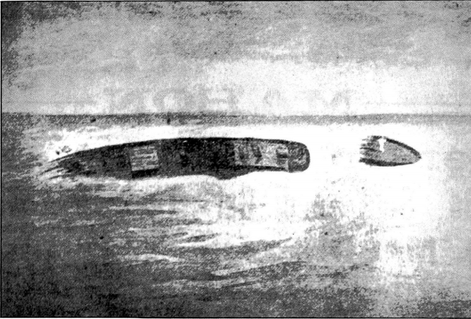

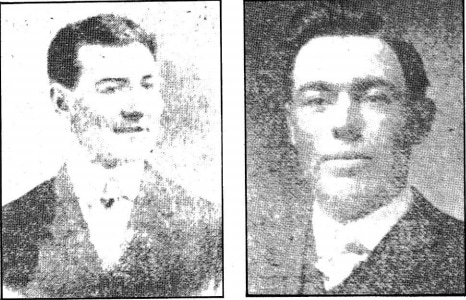

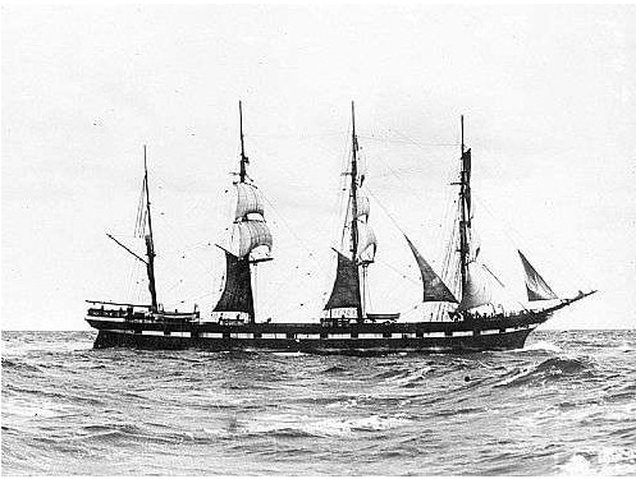

Note: This is part two of our ongoing series documenting some of the ships which were wrecked during the November Gale of 1906. For our first post, click here. A Worldly Crew Just as was the case with the Turret Bell, the Sovinto was a cargo ship which had seen service over its lifetime delivering goods to all corners of the globe. Unlike the Turret Bell, however, the Sovinto was a four-masted barque, renowned as a sailing ship. It had been built by Barclay, Curle & Co, Ltd., of Whiteinch, Glasgow, and was owned by a Finnish owner at the time of the wreck. It measured 61m in length, and weighed 1600 ton. It was commanded by a Captain E.K. Wiglund, and boasted a Scandanavian crew of twenty-one men. These men were natives of Norway, Sweden and Russia, and only the Captain alone was able to speak English. The Sovinto had sailed out of Campbellton, New Brunswick on the morning of Sunday, 4 November 1906 carrying a load of a million and a half feet of lumber, and was headed for Australia. The November Gale Readers familiar with the November Gale of 1906 will recall that this storm was one unprecedented in previous maritime history. It was a storm that could not have been predicted, for The Guardian of 5 November 1906 wrote that "even weather vanes were deceived. The barometer gave no warning; the weather possibilities conveyed no hint of more storms..." Despite this, the November Gale raged on for almost two weeks, and dumped eight inches of rain upon the area. Even as the Sovinto set sail there was no indication of foul weather ahead of them, the skies being fair in Campbellton, and it was not until Sunday evening that they encountered heavy seas and strong north winds. These winds developed without warning and with haste, and by the time the Captain and crew realized that they had sailed into the tempest, it was too late for them to resist it. Gale force winds ravaged the helpless vessel, and as the winds increased, the jib and foretopmasts were torn to pieces; the upper topsail was blown away, and the starboard anchor broke loose. Adding to their difficulties, their cargo had shifted to the starboard side, causing a great pitch to the deck. Without delay the Captain ordered each man a life buoy for his own safety. By Monday morning Captain Wiglund had shifted the course to south-west in hopes of riding the storm down wind. They maintained this position until about 3PM, by which time the crew had finally gotten the anchor up and had cleared much of the deck load. They then turned the ship onto a starboard tack to avoid the Magdalen Islands (les Iles de la Madeleines).  The Sovinto, run aground. The Sovinto, run aground. Panic at Priest Pond On the evening of Tuesday, November 6th, the lookout reported waves breaking on the leeward side, indicating shallow water. The man on the sounding line reported only seven fathoms (approximately 13m). The Captain then gave the orders to drop both anchors, but the order came too late as the ship ran heavily aground on the rocky bottom of Carews Reef off Priest Pond before the starboard anchor could be dropped. The ship was lodged about 180m from shore. As the ship ran aground, one sailor, named Gerwick, was tossed into the sea and was cast adrift. As is detailed in the Historical Sketch of Eastern Kings, by some miracle he was able to reach the shore in the inky darkness, in the face of the abundance of hazardous wreckage which presented itself in the roiling waters. Despite the late hour he scrambled up the cliff side and raced to the only light in sight, the still burning lantern in a distant window. This, it would turn out, was the home of a Mr. Joe Rose. Gerwick pounded fiercely upon the door of the home, but when Mr. Rose came to the door he could not understand who this man was or from whence he had come, for he spoke no English. It was only through sheer repetition of the word “barque”, which is an English loan-word for a type of ship, that he was finally able to convey the tragedy of the wreck.  The wreck site today. The wreck site today. A Desperate Dawn When the ship struck the reef, it was lodged broadside and perpendicular from the shore, making it impossible to launch the lifeboats. Large waves were washing over the deck and the rigging was coming loose. Captain Wiglund called for the crew to be assembled in the starboard cabin, which was still dry and above water. Seventeen men were assembled, leaving four missing; one being Gerwick. The other three, one of them named Kumlander, were trapped on the bow of the ship and unable to reach the cabin. The storm continued to rage, and sometime during the night the ship broke in two, spilling the entire cargo of lumber into the waves. By daylight on Wednesday the shore had been littered with lumber and debris from the wreck, and the wind and waves were so powerful that they sprayed up and over the cliffsides of the shore. A group of onlookers and rescuers had gathered on the shore, and despite the spray and mist, the men on shore were able to see the men still remaining on the wreck, clinging to the deck. A sailor washed ashore that morning still wearing his life buoy. He was badly mangled by the lumber being tossed about in the waves, but still alive. Attempted Rescue Shortly after, the men still remaining on the wreck attempted to launch the life boat, only to have it fill with water within minutes. Seven men drowned as a result; one was only twenty feet from shore when he was swept under, and another was thrown against a flat rock and then pulled under before help could reach him. Seven made it to shore, despite being badly injured. Two others were washed back onto the wreck. One other was swept onto the bow of the ship, left to join his three comrades who had been trapped there since Tuesday night. By Thursday morning, November 9th, only three men remained on the ship; the two souls who had been washed back onto the wreck after the failed life boat attempt, and the twenty-two year old named Kumlander, the lone man who remained clinging to the bow. His three companions had been swept overboard during the night. News of the wreck had spread overnight, and the Stanley, a steamer from Souris had been given order to come to the rescue. Daylight found a large crowd of spectators and reporters from as far away as Charlottetown, all of whom braced themselves against the howling wind and surf to watch the spectacle unfolding before them. A crowd had formed on the shore as well, consisting of local fisherman and those who had been pulled from previous wrecks (The Olga and The Orpheus) earlier in the week. These men knew the sea well, yet were powerless to help in the surging waters. All hopeful eyes looked eastward for the arrival of the Stanley, but due to treacherous currents and winds, she never arrived.  A portion of the Sovinto's crew. Kumlander is holding the life buoy, Captain Wiglund stands in the center. A portion of the Sovinto's crew. Kumlander is holding the life buoy, Captain Wiglund stands in the center. A Heroic Effort It was then that two young fisherman, Duncan Campbell and Austin Grady, both of East Baltic, noticed that the hull of the ship had shifted sideways somewhat, enough to break the force of the waves, if only slightly. Choosing to capitalize on this opportunity, they decided to attempt a rescue using a dory. They launched the small boat into the water, and from the outset struggled to keep the bow headed into the water. Eventually they were able to reach the hull despite an easterly current. The two men clinging to the hull were rescued, and repeated attempts were made to save Kumlander by throwing him ropes. Numerous attempts failed, and the risk was too great to leave the small shelter of the hull. To Kumlander's certain despair, they were forced to head back to shore, leaving him as the last remaining man on the wreck. By Thursday evening, Kumlander had been without rest, food or water for over forty eight hours. He was desperate now, and rather than spend another night clinging to the bow, he took hold of a nearby plank and jumped into the churning sea. He was caught in the current and tossed around the hull before being swept off in a large wave towards the rocky shore. Those on the shore chased after him with ropes, and he was luckily able to catch one. He was briefly dashed across the rocks as his rescuers pulled him ashore, but finally the ordeal was over.  Austin Grady and Duncan Campbell, as they appeared in the Daily Patriot, November 29, 1906. Austin Grady and Duncan Campbell, as they appeared in the Daily Patriot, November 29, 1906. The Aftermath Of the twenty-one men aboard the ship, twelve lost their lives. Those who survived were taken to local homes to recover, although some later died of tuberculosis. Their burials were paid for by Lloyd's of London, who were the insurers of the vessel. Eight of the bodies were buried in the graveyard at St. Columba parish. As the storm subsided and the tide receded, children played upon the wreck, and rounds of cheese floated ashore. Debris from the wreck was used by locals to build and furnish their homes, and some of these home still remain today. Both Austin Grady and Duncan Campbell received a sum of money from the Patriot, and were later presented with the Carnegie Medal of Bravery for their extraordinary heroism. Today, over 100 years later, the wreck is still visible at low tide, and remnants of the wreckage can still be found. The memory of the Wreck of the Sovinto continues to live on in local folklore, and the wrecksite itself has become a popular spot for Island divers. To discover more about the Island's hidden history, from shipwrecks and rum-runners, wishing wells and ghost stories, visit the Red Rock Adventure Company home page, and learn about all the touring opportunities which we offer. This project is made possible through a partnership with the Red Rock Adventure Company and theSourispedia Project. Click here to read about The Wreck of the Sovinto with complete intext citations.

Townshend, Adele. "The Wreck of the SOVINTO" The Island Magazine 1978: 36-39. Print. Watson, Julie V. Shipwrecks and Seafaring Tales of Prince Edward Island. Hounslow Press: Toronto, 1994. Wrecksite. "SV Sovinto (+1906)" The 'Wrecksite. Oct 1 2012. Web. Feb 8 2013.

3 Comments

11/18/2017 12:46:24 am

I felt loneliness upon reading the tragic story of Sovinto. I'm proud of those men who helped the shipwreck survivors. Not all people can risk their lives for the sake of others. There are similar stories from the past just like this one. In the past, many ships were destroyed and sunk by tremendous storms in the sea. Millions of fortunes were wasted and buried along the fragments of these shipwrecks. In a documentary I saw on the television last night, there is numerous fortune like gold, silver, and other expensive things are buried under the sea that still needs to be discovered.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed