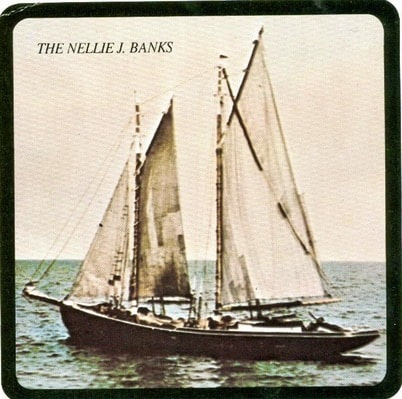

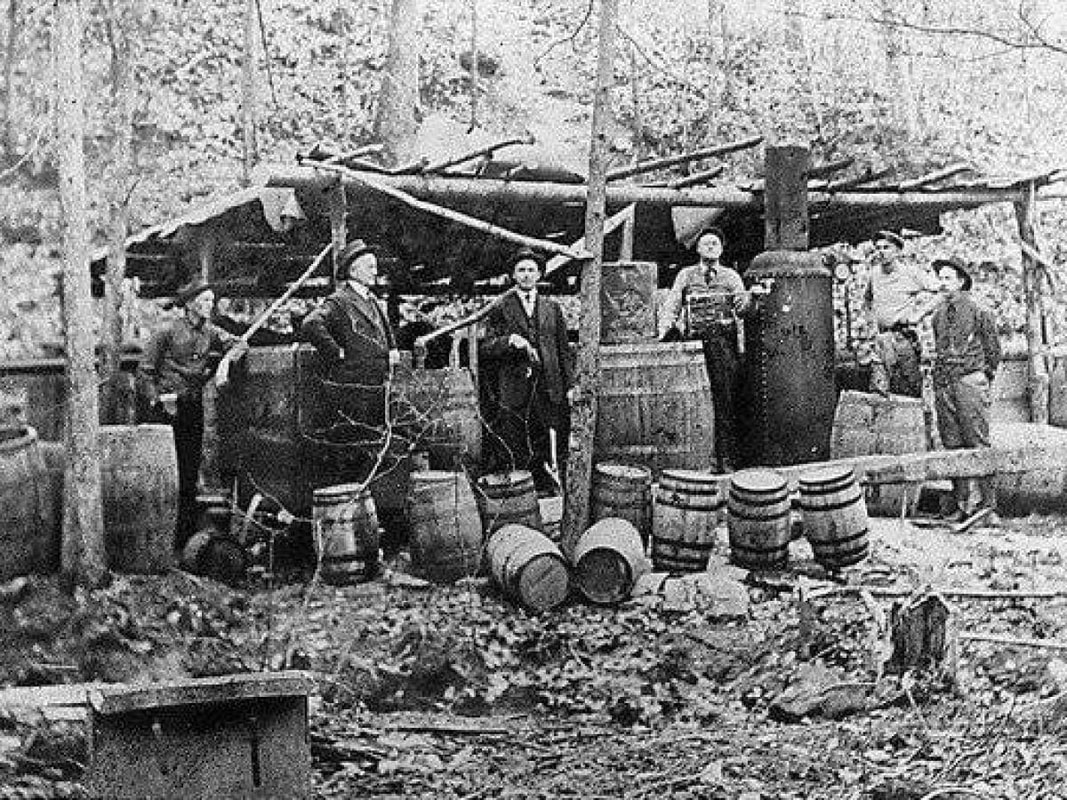

Before the Scott act was put into place around the turn of the century, many small shops and taverns in the area sold liquor in abundance. Pictured here is Alexander Robertson's General Store, Red Point, circa 1904. Before the Scott act was put into place around the turn of the century, many small shops and taverns in the area sold liquor in abundance. Pictured here is Alexander Robertson's General Store, Red Point, circa 1904. EARLY DAYS OF LIQUOR In years gone by you never had to venture far to find a drink, and in that respect little has changed over the years. Whether it be at a kitchen party or wedding reception, at the wharf, or even at a wake, Islanders are known to take a sip of the good stuff when they feel the time is right. Such is tradition, and it is a tradition that dates back to the earliest foundations of the Island community. At the time of Souris’ founding, not unlike any other community, it was the farmers and merchants who kept the villages alive. And in those days, to those who had a license to sell liquor, it was just another profitable commodity in their store, tavern or hotel (1). But that’s not to say that liquor wasn’t a problem; in those days of flowing taps and loose regulation, it was often the smell of liquor which hung like a pall over a town. Even by the 1860s there was vocal opponents to the open sale and consumption of alcohol, but those who advocated temperance were only small voices awash in a sea of booze. At this time there were nearly a dozen shops and taverns selling alcohol between Souris East and Souris West, and as such, it was said that there is “little wonder Souris has such an unsavory reputation in many parts” (1). Yet the residents of Souris weren’t solely to blame for the alcoholic epidemic which gripped the area. As a seaside town with a sturdy harbor, Souris played host on a nightly basis to countless sailors and seamen who would come ashore in search of drink and disorder, and those businesses which depended on them were all too willing to oblige. It is said that liquor flowed six days a week out the front door the town’s taverns, and that even on Sunday the back doors were never locked.  Working fishermen in Souris Harbour, ca 1920s. Working fishermen in Souris Harbour, ca 1920s. SAILORS TAKE THE SHORE As Townshend writes, “the impact on Souris of the American fishing fleet was probably to make fighters of many of the youngsters who grew up between 1865 and 1885… liquor was cheap and easy to obtain and many of those who drank wanted to demonstrate their fighting abilities. It was a period when the merchants shuttered their windows every night and unbarred them every morning” (1). One particularly unruly incident occurred in August of 1887, when a major storm forced all of the American fleet inland into the harbor. A staggering 800 foreign fishermen came ashore that evening, easily outnumbering the residents of the town. The Chief Officer on duty, who had been sent to keep the peace, was drugged by the fishermen, and in his absence the men were free to behave as wildly as they pleased. They even cut the buttons and badge off of the poor Officer’s uniform, and later, when the incident was reported, he stood trial for neglect of duty (1). Another occasion, now known as “Axe Handle Night”, illustrates the volatility of the situation in Souris when liquor and sailors mixed. The incident began near the old Carleton store around 8:00PM (1). Joseph Doyle, a Souris merchant and banker, was spotted being attacked by drunken sailors. James Dunphy, a Souris saddler, ran to his rescue, and soon they were both badly injured. The alarm was raised, and a throng of locals took to the streets against these rioting fishermen. Both sides armed themselves with sticks and axe handles (1). Further clashes ensued, but the Souris locals were successful in driving these unruly men back towards the wharf. Several rioters were captured and locked up for the night (1). Things did not end so well for everyone, however. One sailor, a Joseph Strople, was fleeing from those Souris men, and in his drunkenness did not make the turn onto Breakwater Street. Instead he careened over the bank, near the present day Sailor’s Memorial, and tumbled to his death upon the rocks (1). The rioters who were arrested that night were each fined $50, which was considered to be a large and excessive fine at that time. Other charges included “fighting on the shore on the Sabbath”, for which those found guilty were charged $2, and being “drunk and disorderly”.  The Scott Act so vehement support and opposition from the public and from religious institutions. The Scott Act so vehement support and opposition from the public and from religious institutions. THE SCOTT ACT Such incidents were no doubt on the minds of legislators in 1878, when Senator R.W. Scott brought in the Canadian Temperance Act, the first measure of the Federal Government to control the sale and use of alcohol. It passed the same year and became known as the Scott Act. It provided total prohibition on liquor sales in any area of the country, except for medicinal use (1). In June 1901, Prince Edward Island became the first province to adopt the Scott Act. Interestingly, the Island was subsequently the last to repeal the act in 1948. This meant that for 47 years alcohol was prohibited in the province, and ironically it was arguably during those 47 years that alcohol most freely flowed. The effectiveness of the Scott Act was deemed questionable from the very beginning, and according to the Examiner, “The Scott Act is in operation or rather was adopted...but is as dead as Julius Caesar and ten illicit liquor shops are in full blast from which foreign fishermen get full supplies and thereafter make nights hideous with their shocking profanity, fighting and general rowdyism” (1). J.J. Hughes, Mayor of Souris and Liberal Member of the House of Commons, reported “that every possible device was being used to circumvent the provincial laws. Liquor was flooding into his province hidden in flour barrels, boot boxes” and every other conceivable manner of concealment (1). It was from these methods that rum-running, the practice of smuggling contraband alcohol to shore, developed into the booming and raucous industry it became in the early half of the twentieth century. There are few alive today who fully remember the impact that rum-running had on the Island, but it is still well known that the North shore of King’s County, with the help of ships like the Nellie J. Banks, was one the focal points of the whole ordeal.  The famous Nellie J. Banks, under the direction of Captain Dicks, was the leading figure in rum-running off of the north side of Eastern Prince Edward Island. The famous Nellie J. Banks, under the direction of Captain Dicks, was the leading figure in rum-running off of the north side of Eastern Prince Edward Island. RUM RUNNING Prince Edward Island’s enactment of the Scott Act was reason enough for Islanders to seek out other means of procuring and imbibing the dangerous drink, but they soon set their sights on a bigger target. In 1920, when the United States enacted prohibition, rum-runners found themselves poised to reap a fortune by supplying smuggled rum to the parched hordes of Americans who now found themselves dry. Fate, it seemed, had dealt island smugglers a perfect hand. The little-known island of St. Pierre and Miquelon, which belongs to France, was one of the only jurisdictions in North America which was not subject to prohibition. And as luck would have it for Island rum-runners, ships departing from St. Pierre and Miquelon were within close proximity to Prince Edward Island’s waters. Once this connection was made, the stage was set, and Islander’s began smuggling rum at an unprecedented rate. The set-up was clever in its simplicity; a twelve-mile limit had been established by the provincial government, and anyone found to be in possession of alcohol within this limit was under the jurisdiction of Prince Edward Island. The waters outside of twelve miles though were anyone’s game. Ships from St. Pierre and Miquelon would be scheduled to arrive at a certain time and place, just outside the limit and always under the cover of night. Local men, typically on fishing boats, would then sail out to meet the ships, buy the rum, and head back to shore. Great care had to be paid though, lest they be apprehended by the authorities, and in response to this ever present threat all manners of cunning schemes were devised to evade authorities. One such scheme was to arrange to meet the French ships based upon the cycles of the tide, so that when the rum was loaded onto the Islander’s boats they would reach the shore at low tide. Then, instead of moving the rum as the police may have expected, it would be buried in the exposed sand bar and hidden away, safe from accidental discovery or interference. That way officers found only empty vehicles at their checkpoints. Several nights later, when there was no tip-off of any rum arrivals, the rum-runners would return to the beach and unearth their buried treasure. FATE’S PERFECT HAND But the most clever method of all was one recalled by an old timer who was only a young boy at the time, who was out on one of his first runs when they were intercepted by a police boat. All of the bottles of rum had been hidden in burlap sacks of sugar, but the boy was convinced that the police would still find them. Panicked, he threw all the sacks overboard, where they sunk to the bottom. This ensured that the police found no trace of rum, but the rum-runner was so angry that he threatened to throw the boy overboard. He was spared only by a disturbance which the Captain noticed upon the water. The boy looked, and to his disbelief he saw that the sacks which had sunk to the bottom were now floating alongside the boat. All of the sugar had slowly dissolved, and the rum and floated back to the top. The boy had saved the day, and a new method had been discovered to evade the watchful eyes of the police, something which continued to the very end of prohibition on Prince Edward Island in 1948.  Those men who could not ply the trade of rum running found moonshine to be a more viable option. Those men who could not ply the trade of rum running found moonshine to be a more viable option. MARVELOUS MOONSHINE But for those who would not, or could not, take to the sea in pursuit of a drink, moonshining proved to be a viable option. Moonshine could be made at affordably at home, and could be done without attracting much attention from neighbours or law enforcement. In actuality, the greatest impediment to a budding moonshiner was not police interference, but the disapproval of an on-looking wife or mother, aghast at the use of the kitchen utensils, particularly on a Sunday. And while methods varied somewhat, the end result was always the same. Corn, potatoes, apples, even beets could be used as a base, and when distilled would yield a product which would tolerably pass as moonshine. Molasses and brown sugar were always key ingredients as well. As Knight writes, “the culture of moonshine is strong in rural Canadian areas where people are used to making everything from scratch, cherish a healthy disrespect for politics and the law, and have plenty of acreage to work in total obscurity” (2). Such was the case in eastern Prince Edward Island as the Scott Act held in place. Stills could be set up in kitchens, basements, or backwoods, and with the right care and attention the shine would be flowing in no time. One had to be protective of their stills though. To have a known still opened one’s self up to theft from those desperate for a drink, be they neighbours, teens, or vagabonds. The problem was not easily solved though, as it was not merely as simply as bringing the shine into the house. To do so would be to risk to discovery by the police if they did search your home. Instead, inventive methods were devised in order to keep to the shine hidden in plain sight. One such method involved hinging certain steps on the stairs to create a hiding place. Another common method was an old fashioned burial; this was one of the safest methods, although you remained open to theft, or loss due to forgetfulness. It is said that one infamous moonshiner from the northside buried every ounce of shine that he made down by the stream, in order to hide it from his wife. When word got out about these burials, it didn’t long for people to begin searching for the shine late at night. Sometimes they got lucky, and this shiner was forced to hide them better and bury them deeper the next time around. To this day, down near the spring, there remain divots in the ground where the shine was once concealed, and new holes appear from time to time, but whether they are dug out of desperation or curiosity remains unknown.  Myriad View Distillery (Tripadvisor Photo). Myriad View Distillery (Tripadvisor Photo). PRESENT DAY PRACTICE Unlike rum-running, which saw its glory days come and go, moonshine is ever popular and readily available on the Island to this day, and eastern PEI remains a leader in the production and consumption of the drink. And while the homemade, under the table stuff remains a perpetual staple in Island homes, the Myriad View Distillery in Rollo Bay offers PEI’s only legally produced moonshine, which is sold across the Island and marketed as Strait Shine. It is potent stuff, and it has served as a wonderful way to introduce those ‘from away’ to a part of an Island tradition which they may never have had the opportunity to experience otherwise. References: 1. Townshend, Adele. Ten Farms Become a Town. 1986. Print. 2. Knight, Ivy. "Moonshine Runs Through the Veins of Prince Edward Island". Munchies-VICE. 22 Sep 2014. Web. To learn more about the Red Rock Adventure Company, or to book a tour, click here.

You can click here to find us on Tripadvisor and read our reviews.

5 Comments

9/27/2018 02:06:04 pm

This web site is really a walk-through for all of the info you wanted about this and didn’t know who to ask. Glimpse here, and you’ll definitely discover it.

Reply

Lloyd Bruce

2/11/2020 06:27:34 pm

Excellent story ,well written

Reply

4/27/2020 07:29:19 am

When your website or blog goes live for the first time, it is exciting. That is until you realize no one but you and your.

Reply

1/31/2021 06:59:55 am

Very informative article. I live on 45 acres in eastern PEI. Moonshine was produced and distributed on a large scale from my property. I'm constantly finding evidence of moonshine and stills in the forest. I've heard many interesting stories from the locals. I love reading about the cultural tradition of moonshine production and rum-running on the Island. Thanks so much, WB

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed